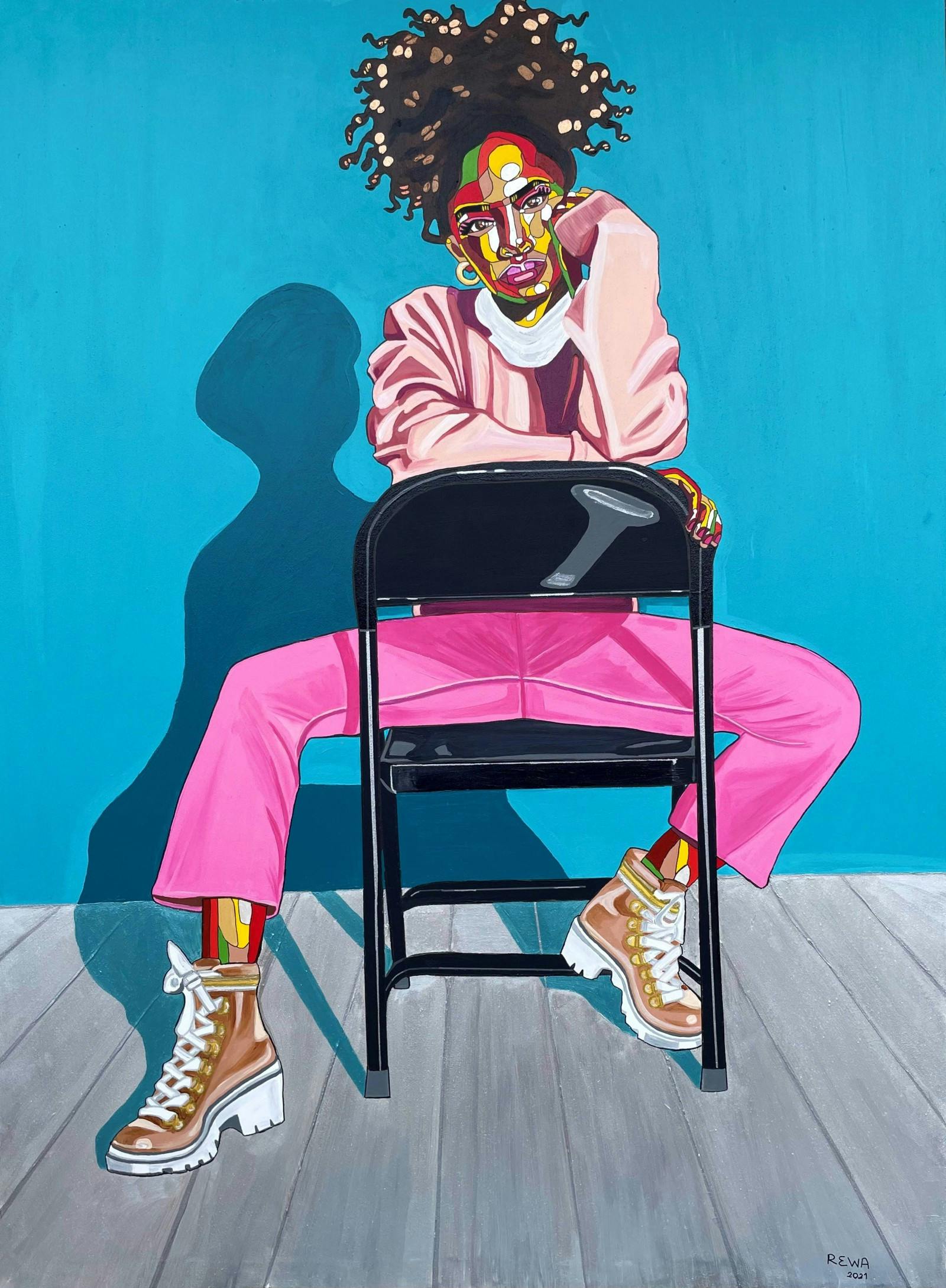

After the Signs Come Down

In examining how white South Africans grapple with belonging in post-apartheid South Africa, Sydelle Willow Smith’s somewhat autoethnographic photographic series, Un/Settled, meaningfully poses more questions than it answers, writes Leslie M. Wilson.

Antique store, Hermanus, December 2017 (Image: Sydelle Willow Smith)

Between nautically themed shelves in the scenic seaside town of Hermanus in the Western Cape province of South Africa, bold white letters against a brown background read: “NET BLANKES. WHITES ONLY.” This once common sign of apartheid rests now slightly askew in Sydelle Willow Smith’s photograph, ‘Antique store, Hermanus, December 2017,’ echoing subtly the tilted head of an adjacent doll wearing a sailor’s uniform. The doll’s blue eyes stare out blankly, while scuff marks on his surface suggest he has seen better days.

Another sign lurks in the photograph, hidden behind utensils and plates of incomplete dining sets on the lowest shelf. In large capital letters, it reads: “MUSEUM.” Yet another space for encountering often troublesome old things.

Of all the odds and ends on view in Smith’s photograph, we might ask: Who would still want this stuff?

These questions about stuff are really questions about history. What do any of us want of the past? To what do we lay claim? Objects? Land? Nation? Identity? Status? We so often discard things when trying to move on, but how can we draw a line under the past when the past is not done with us?

We so often discard things when trying to move on, but how can we draw a line under the past when the past is not done with us?

The antique store image is from Smith’s ongoing photographic series, Un/Settled, which serves as a reminder that apartheid’s racist objects, architecture, urban geographies, and logics have proved tenacious in their endurance. Despite the removal of the official markers of apartheid, apartness remains. Apartness in particular — a literal translation of apartheid — is something white South Africans still grapple with and that Smith explores in the series. Un/Settled asks of white South Africans: What does freedom mean when so many of the structures of racial, class, gender, and linguistic privilege and exclusion remain, even though the signs came down?

Through portraits, interviews, and observational studies of people and places, Un/Settled examines how white South Africans see themselves and negotiate contemporary life. Smith intentionally called on ethnographic methods in her approach, using ethnography — with its colonial legacies — to “turn the colonial gaze inward.” From her own contemplation of apartness, Smith was aware that her whiteness granted access to what is said only behind closed doors. It allowed her entry into homes and spaces of leisure often secluded by high walls and elaborate security apparatuses. Deftly, Smith positions viewers on the inside looking out, as well as on the outside looking in. By embracing the access afforded by whiteness to interrogate whiteness, she brings close what many will only see at a distance if at all.

In the photograph ‘Kalahari Rest Stop, November 2016,’ Smith enters the exclusivity of the swimming pool, where the turquoise blue water offers a reprieve from desert temperatures and sunburn. On that scorching day, Smith was seeking relief for herself in the water. But the scene, in which a group of bronzed, white bodies gather in the pool under a big blue sky, also announced its apartness.

Kalahari Rest Stop, November 2016 (Image: Sydelle Willow Smith)

In ‘A Day at the Horse Races, Cape Town, January 2017,’ viewers find themselves amid revellers attired in the loose formality of hats, dresses, and button-downs customary to the track. The convivial sea of people appear so at ease, like they all know each other. Some stand on benches to get a better view of the races, as if they own the place.

A day at the horse races, Cape Town, January 2017 (Image: Sydelle Willow Smith)

Smith’s series plays with closeness and distance in its examination of white spaces. For instance, ‘Christmas Day, Hermanus, December 2016,’ shows a row of immaculate contemporary and Cape-Dutch-style houses nestled into the mountains. A line of greenery separates the viewer from the houses set into the middle ground of the photograph. The composition invites questions: Who lives there? In possessing some of the best views in town, do they feel privileged or isolated?

Christmas Day, Hermanus, December 2016 (Image: Sydelle Willow Smith)

‘Spring Garden, Hogsback, October 2018,’ features a large bay window that offers a triptych of the kind of grand landscape that has long inspired plein air painters and tourist agencies. Viewed from the darkened interior of the house, the landscape glows, almost like the glass case displays in natural history museums. It is as if this scene, too — like the stuff in the antique shop — is frozen in time. Against the mountains in the distance and vegetation, through the windowpane at the left, a black man mows the lawn. Something about the scene suggests strongly that this man owns neither the land that he works nor the house from which he is seen. But what is that something? How do we know so little and so much at the same time?

Spring garden, Hogsback, October 2018 (Image: Sydelle Willow Smith)

Smith makes use of public spaces, social media and the internet to exhibit Un/Settled. The attendant commentary from those contexts has also informed how she has come to understand the project. By displaying this work in places like Company’s Garden, a colonial-era public park in the Cape Town city centre, or at a traffic circle in the city’s Waterfront district, Smith further inserts the series directly into the public sphere in hopes of spurring conversation and reaction. Un/Settled seeks a reckoning over what it means to belong to South Africa and to ask: How might claims to objects, land, nation, identity and status be reconciled with the traumatic past and present?

Eliza, High School Student, May 2018, Cape Town (Image: Sydelle Willow Smith)

Smith finds optimism especially in the words of her youngest subjects. Running counter to the common tautological refrain that apartheid just “was what it was,” a student named Eliza spoke to Smith of “historical debt,” “responsibility,” and a commitment to stay in South Africa to address questions of how the country’s citizens share its resources and engage with one another. In the portrait, Eliza stands in her blue and plaid school uniform in an empty gymnasium, her arms crossed in a posture implying self-assurance. The questions that linger beyond the photograph’s frame are how these commitments translate into action. What does real change look like? How can it translate into material improvements?

Albie Sachs, former Constitutional Court Judge, Cape Town, May 2018 (Image: Sydelle Willow Smith)

In the interview accompanying his photograph, famed jurist Albie Sachs also grapples with the question of real change. He expressed concern about the continuities with the past, asserting, “The next generation are picking up the remaining elements of white hegemony, with an assumed sense of superiority and white living conditions.” In this way, Sachs suggests, South Africa’s efforts to eliminate racism have been only partially successful: The political and legal system has been dismantled, but race continues to overdetermine public life and mediate social interactions.

West Coast Drive, November 2014 (Image: Sydelle Willow Smith)

In ‘West Coast Drive, November 2014,’ a billboard in the shape of an arrow points passers-by to a destination—or ostensibly a person, a blond woman reclining by an immaculate swimming pool—and a promise of an easy living. The text below her reads: “Calming & enchanting.”

Set against seemingly endless, half-parched grassland, the billboard has an absurd, mirage-like quality. It seems a symbol of fantasies and myths so often accompanying national claims. The billboard suggests that somewhere further down the road, beyond the frame, there lies reprieve.

Ultimately, what Smith offers in Un/Settled as a body of work is a model for interrogating whiteness. Revealing that so much of the past is still present, the images, and how Smith has solicited engagement with them, invite reflection on uncomfortable continuities. To break those enduring structures and patterns requires finding answers, as uncomfortable and messy as that process might be.