Proximal Blackness: A Reflection on Race Beyond Borders

Zora Neale Hurston’s famous 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” brings into sharp focus the many ways geography impacts the experience of Blackness. In this lead feature, writer Lindokuhle Nkosi uses Hurston’s words to reflect on the Season 2 finale of our podcast, Race Beyond Borders, in which our outgoing host Sebabatso Manoeli-Lesame and incoming host Nigel Richard revisit the season’s sonic journey.

“I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background” is an often-used sentence, so frequently quoted that the threads binding the many facts, feelings, and fictions contained in this 13-word-sentence are almost bare and fraying. These words, which make their first appearance in Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay “How It Feels To Be Colored Me,” does some heavy lifting. Stark and unrelenting, it captures readers in the crosshairs of a severely darkened silhouette in a sea of glaring whiteness.

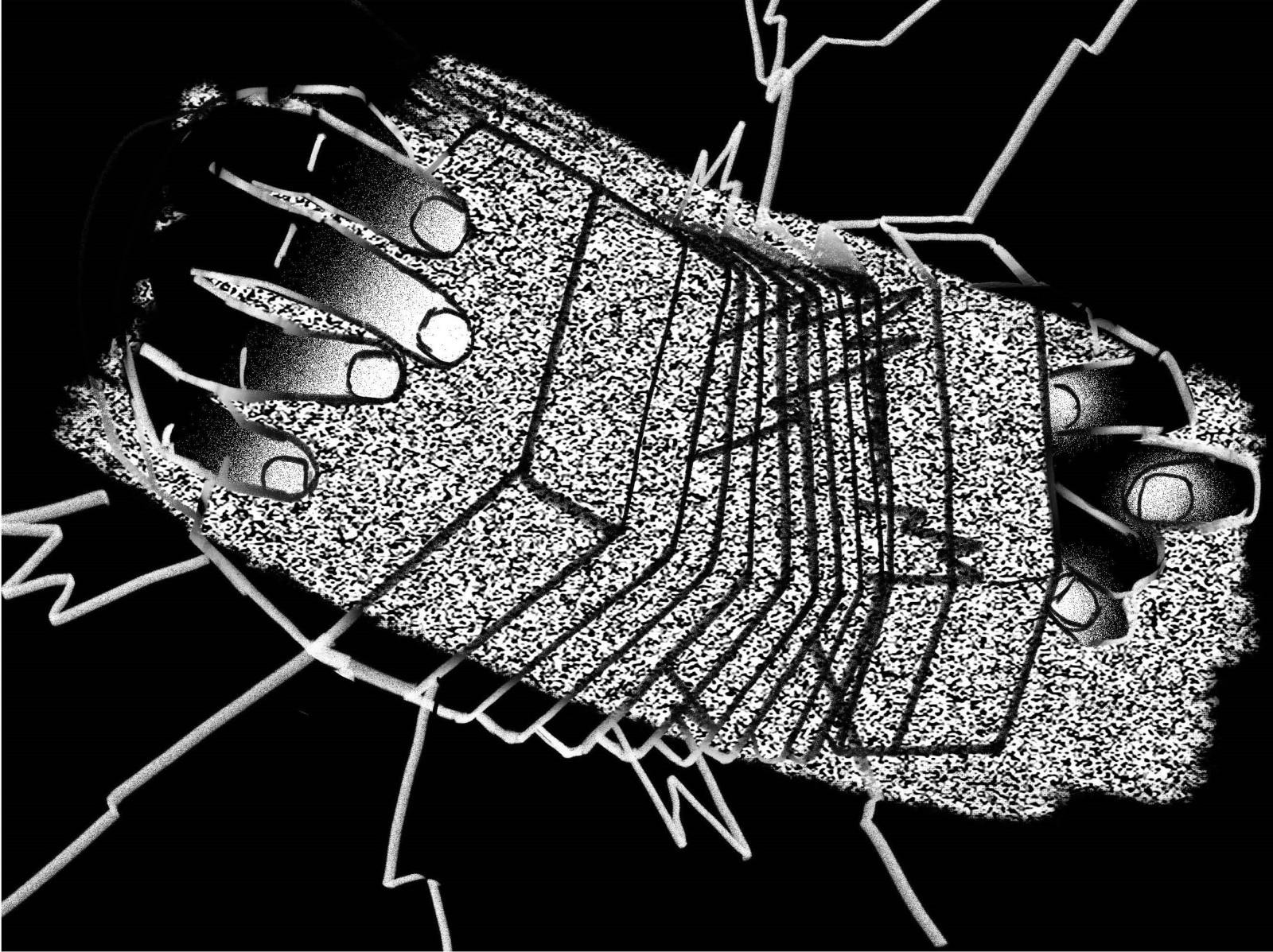

In contemporary artist Glenn Ligon’s “Untitled: Four Etchings,” Hurston’s words are repeatedly stencilled on a long white panel. The first line is clear to read. The letters are spaced politely away from each other. Each line making tidy angles on the canvass behind it. As the viewer's eyes travel down, the Black ink begins to bleed outside of the letters containing it, staining, and blotting the white backdrop until it is no longer sharp. The white is no longer unsullied. The boundaries are threatened.

“I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against A Sharp White Background: An Elegy,” a poem by Morgan Parker, also references the popular line but unlike Ligon’s treatment, Parker distances them, putting words on separate lines, breaking the phrase apart, interjecting as if seeking affirmation from Hurston.

Although Hurston’s words aren’t featured in season two of Race Beyond Borders, the notion of proximal Blackness, which is at the very heart of Hurston’s words, is. Throughout the season, host Sebabatso Manoeli-Lesame, who also serves as AFRE’s executive director and the editor-in-chief for Moya, took listeners on a sonic safari from the Caribbean, Oceania, and Martinique to Colombia, Italy, and Iran, traversing the sometimes shifting and limiting popular notions of Blackness.

In the final episode, Sebabatso sat down with the incoming host and AFRE’s Fellowship Director & Facilitator Nigel Richard, to reflect on the season’s journey and the ways geography impacts the experience of Blackness.

“Episode 6, the episode about Mexico and the Dominican Republic, really spoke to me,” Nigel said, referring to the Black Royalty and Joy in Latin America episode in which listeners meet Miguel Valerio, a scholar of the African diaspora in Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula. In the episode, Valerio explains how he’s been read and racialised differently in his travels across Latin America, sometimes without his own participation.

“The speaker talked about how his race changed depending on his proximity to whiteness. How interpretations of his ‘whiteness’ or ‘Blackness’ is sort of proximal to the geography he was in.”

Nigel is a mixed American--his father is white and his mother is Black--based in New Jersey. Well-travelled, he’s been unpacking his experiences with race in different parts of the world his entire life, including the nine years he spent working as an educator in South Africa.

“In South Africa, I moved into a whole different categorisation either being called ‘white’ or ‘Coloured’. Being called ‘white’ really threw me,” Nigel said. He was forced to contend with this racialisation even in his classroom.

“I was a classroom teacher [and] I kept talking about ‘we’ to my all-Black students, and referring to things as a Black person, as I would in the U.S. One day, a student raised their hand and said ‘Mr. Nigel, I don't understand what you’re talking about, you’re not Black’.”

In a moment that appears on the face of it, almost a reversal of the Hurston line, Nigel was made to feel less Black against a stark Black backdrop. At that moment, like many moments before in his life, how he understood himself in the world did not translate in an altered political terrain. What happens in that space, when the language we develop to create belonging in the world is limited and in turn becomes limiting?

In 2015, confronting anti-Black racism and redefining Blackness became mainstream conversation in South Africa as the student-led movement Rhodes Must Fall (RMF) forced the country and its institutions to interrogate the legacy of colonisation and institutionalised anti-Black racism. An interesting consequence of RMF was a mass interrogation of political Blackness. The students put language to an identity friction experienced by the non-white people who fell under that blanket term and challenged the epistemological violence inflicted on Black students and staff.

At the same time, in the United States, the extra-judicial killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed Black 18-year-old from Ferguson, Missouri, galvanised Americans around the Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement and later the Movement for Black Lives. What happened to Michael Brown gave birth to a movement that set the nation on course for a continuous public reckoning on race that stretch beyond conversations of police brutality and the racialised carceral system.

Both movements erupted in countries that self-describe as democracies, but that also have histories of Indigenous genocide, racialised slavery, and legalised segregation. Both movements challenged the mechanisms that nurture systemic racism and anti-Blackness, namely the centring of whiteness.

“I think sometimes we reinforce and recentre whiteness in our understanding of Blackness because Blackness is often discussed in relation to whiteness,” Sebabatso said. “What happens to Black people who aren't in contact with white people? What is Black life when it isn't mediated through English? What do we call Black people in Martinique? In Italy? How is Blackness understood linguistically in Iran and what are the implications of that? I think I've just been struck by the world of possibilities that opens up when you have different language access points.”

I think sometimes we reinforce and recentre whiteness in our understanding of Blackness because Blackness is often discussed in relation to whiteness.

Sebabatso Manoeli-Lesame

Adama Sanneh was born in Italy to an Italian Catholic mother and a Muslim Senegalese-Gambian father. He describes himself as “an African, European, Italian, Gambian, Senegalese, blue collar, bourgeois, Muslim Catholic, and Black and white man. All of the above, and none of the above either.”

In the season’s first episode Crafting a Black Italian Identity, Sanneh guides listeners through his coming of age as a Black Italian man in a national context marked by this paucity of Black community. Five years ago, he gathered a group of 24 friends and strangers in his Milan apartment. “It was the first time for each one of us to be with more than one Afro-Italian in the same space at the same time,” Sanneh said. That night, the newly assembled group of Black Italians considered whether they might choose a word in Italian to refer to themselves. Ultimately, they chose not to.

“I was struck by Adama’s episode where he just really brought me into the grappling of naming,” Nigel said. “How in Italian some things just don't translate. There just isn't a word for Blackness in the way that it exists in the U.S. context. The freedom that that group found in not naming themselves, was really powerful.”

The naming of things is particularly contentious. We understand the importance of putting language to experiences and that through naming the world, it becomes concrete and the people doing the naming become arbiters of its meaning. To name something is to make it real and significant. And to be able to confer meaning and significance is power. Naming becomes parameter, boundary, edge. And much like our bodies, we are primarily concerned with the names of things when their edges are threatened. When their borders become porous in meaning and confused in function and fact.

Nigel’s encounter in his classroom was not his first confrontation with the ways in which Blackness is codified differently and how its meaning is primarily informed by the politics of the intimate—domesticity, friendship, home. In speaking about being an educator, he recounted the early formations of his identity.

“My political journey started very much in school. My family and I experienced injustice and anti-Black racism in the schooling system. Some of the violence we experienced through the schooling system penetrated our family. I think a lot of anti-Black racism does. Where does anti-Black racism and its harms end up? It ends up in the home. We may experience it on the street or in a boardroom, or in school, but at the end of the day, we come home to our families, and it sits, and it sows, and it festers.”

Where does anti-Black racism and its harms end up? It ends up in the home. We may experience it on the street or in a boardroom, or in school, but at the end of the day, we come home to our families, and it sits, and it sows, and it festers.

Nigel Richard

Zora Neale Hurston did not realise she was Black until her family life was disrupted. Until the boundaries of the intimate were threatened and penetrated. Growing up in the all-Black town of Eatonville, Florida where her mother was a teacher and her father a preaching sharecropper turned Mayor, the only difference between her and the white people who rode through town was precisely that—they rode through town, they did not stay.

Later in life, Eatonville would feature in her writing as a place where African Americans could live as they desired, independent of white society. After her mother died and her father remarried, she was sent away to a Baptist boarding school in Jacksonville, Florida. It is here that she discovered her Blackness. She writes in “How It Feels To Be Colored Me”: “I left Eatonville, the town of the oleanders, a Zora. When I disembarked from the riverboat at Jacksonville, she was no more. It seemed that I had suffered a sea change. I was not Zora of Orange County anymore; I was now a little colored girl. I found it out in certain ways. In my heart as well as in the mirror, I became a fast brown—warranted not to rub nor run.”