Trevor Noah: The Self-Styled Middleman

Amid the evolving political climate and cultural landscape in South Africa and the United States, Trevor Noah has proven adept at weaving his racial identity and outsider status into his personal brand and comedy to achieve mass appeal, writes Khanya Mtshali.

If you happened to have been familiar with South Africa’s budding comedy scene in the 2000s, it would have been inconceivable that one of its fledgling talents would break into the American market just five years after his official debut. It would have been even more unthinkable to imagine that this newcomer would inherit a late-night television show long considered the crown jewel of liberal comic punditry—steering it away from sarcastic rebukes of the “War on Terror” and righteous digs at the conservative talking heads of the Bush years, towards pithy gags produced by a younger, more diverse staff. And after he survived a storm of bad press for tweets that didn’t age well, allegations of stolen jokes, and withering critiques claiming he lacked what it took to lampoon the American political system, it would have been impossible to envision him capping off his seven-year term on late-night TV with the most enviable gig in Washington, D.C.: headlining the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in 2022.

Yet this has been the trajectory of Trevor Noah, the South African comedian who has transcended the industry that first brought him to the United States in 2011. In January, when Noah became the first Black person to win the 2024 Emmy Award for the best variety talk show, I thought it timely to reflect on the unlikeliness of his global success. A self-described racial chameleon, he was schooled in the art of South African gallows humour, finding laughter in grim subjects like social and political failures of the post-apartheid state. Yet, to secure himself a place in American pop culture and liberal politics, Noah has shifted tack to embrace a tamer version of his previous material, using his multicultural racial identity and foreignness in his personal brand and performances to navigate a comedy scene riven by growing ideological divides.

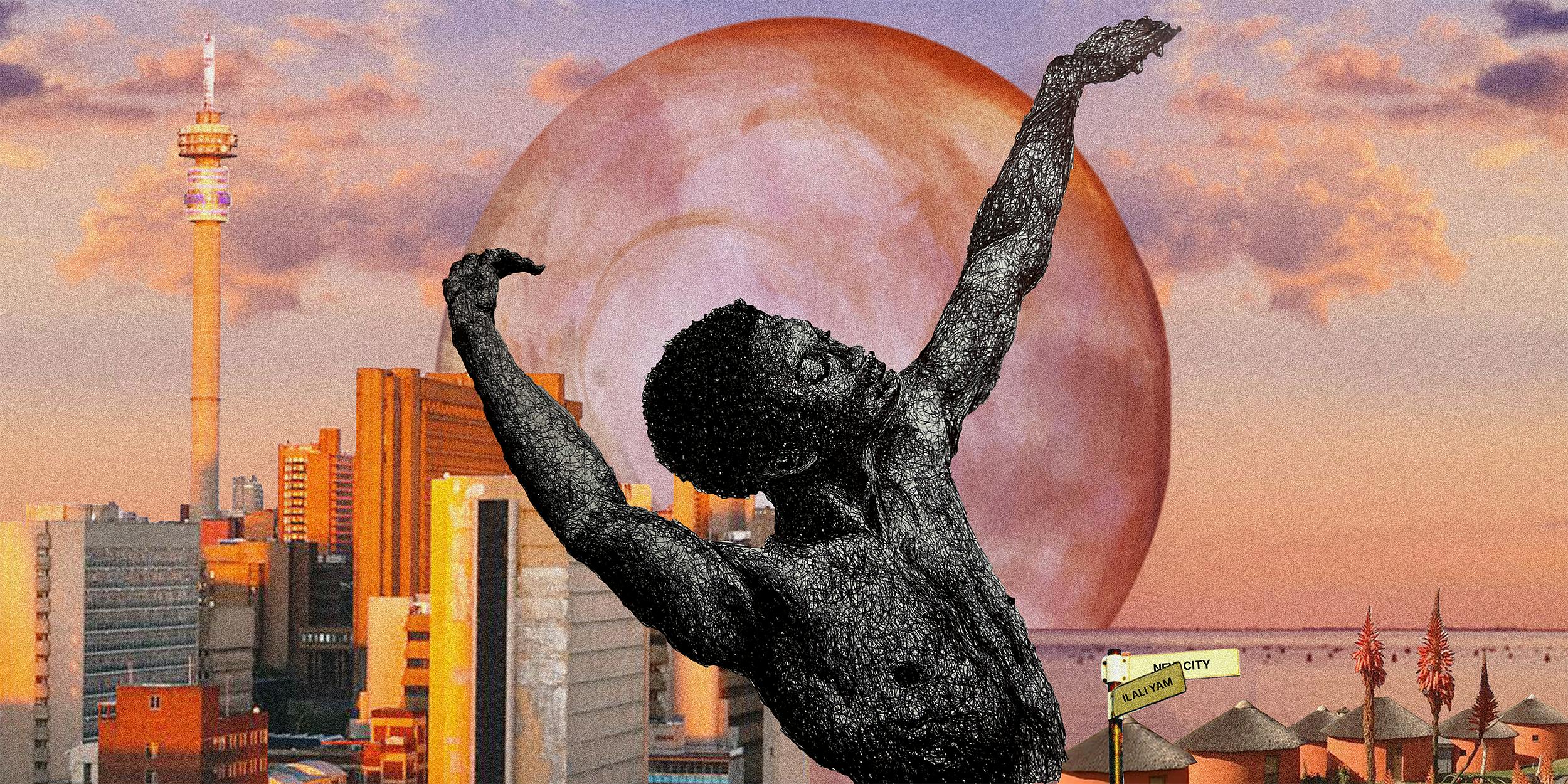

I was in my penultimate year of high school in 2009 when Noah, aged 26, performed his first comedy special, The Daywalker, for two sold-out nights at the Lyric Theatre in Gold Reef City, an enclosed casino-amusement park complex just south of the Johannesburg city centre. Having decided to take comedy seriously only a few years earlier, the opportunity was a step up from his gigs at dingy bars and nightclubs, emceeing corporate functions where risk-averse organisers wanted him to water down his material, and working as a taxi driver. The massive billboard for the show was unmissable, looming over commuters on the M1 highway, one of the main arteries connecting the city. When the DVD hit the shelves the following month, it became the talk of the town, prompting many of us to reenact parts of his set, like the hilarious skit in which Noah delivered a pitch-perfect impersonation of a drunk Nelson Mandela.

The Daywalker, in essence, is an account of a young Noah coming of age against the backdrop of a South Africa experiencing its own growing pains. Born to a Black Xhosa-speaking mother and a white Swiss-German father a decade before the end of apartheid in 1994, Noah’s existence was a crime effectively under the apartheid-era Immorality Act, which, before it was repealed a year after the comedian was born, prohibited interracial romantic and sexual relationships. In the performance, Noah dissects assumptions made about his heritage, poking fun at the confusion he triggered as a person who looked Coloured (a South African racial demographic group of generationally multiracial and multiethnic people), spoke with an accent associated with the country’s newly desegregated public schools, and spent part of his childhood living with his mother and grandmother in the mostly Black township of Soweto. As he explains it, kids in Soweto, believing he was a person with albinism, christened him “daywalker” based on the dangerous myth that people with albinism cannot step into direct sunlight.

Throughout the special, Noah leans on these autobiographical details as a springboard for commentary from multiple perspectives on racial thinking in South Africa. For instance, he puts on what he calls a “Black accent” to parody Julius Malema, at the time president of the Youth League of the African National Congress, and Jacob Zuma, then president of the ANC and the country—playing on claims in newspaper columns that both men were unintelligent for their lack of extensive formal education and the latter’s observance of Zulu traditional practices. Despite having relied on this trope for comedic effect, Noah then blames Malema and Zuma for saying and doing things that caused white people to associate their accents, which is how many Black South Africans speak English, with a lack of intelligence. Within the same sequence, Noah also pokes fun at “half the white women in the country” and “even Black people” for perceiving information, even information that could save their lives, as sub-standard when delivered in a “Black accent.”

The segment, and the entire performance, was emblematic of the way Noah’s particular multicultural upbringing and racial heritage were, and remain, central to his brand and identity as a comedian—enabling him to pose as an outsider with insider knowledge of the supposed parochialism within each social group. In a country with bone-deep racial wounds, Noah used his background to claim a middle ground, presenting himself as an “equal-opportunity offender” who could dabble in racial caricatures and tropes, yet still retain the trust of the group he happened to be making fun of. This put the audience at ease, giving them the freedom to laugh without any guilt: if Noah was mocking everyone, he was offending no one.

The segment, and the entire performance, was emblematic of the way Noah’s particular multicultural upbringing and racial heritage were, and remain, central to his brand and identity as a comedian—enabling him to pose as an outsider with insider knowledge of the supposed parochialism within each social group.

The Daywalker was, at the time, one of the few pieces of South African pop culture that resonated across the country’s colour lines. In my grade, it was common for students to connect across racial divides over films, music, and TV from Europe and the US but not so over local cultural productions. Noah proved to be the exception. Not since Nelson Mandela had a public figure been embraced across such a broad range of South African society. Whereas Mandela fought to eliminate racialism from the fabric of South African life, Noah banked on it, relishing the chance to poke fun at tensions that were still deeply felt in the country.

In his follow-up releases, The Daywalker 2.0 (2010) and Crazy Normal (2011), Noah exuded his usual confidence and charm, along with marked improvement in his timing, delivery, and ability to improvise off the audience’s responses. It was around this time that South Africa’s reputation as the world’s “miracle” democracy began losing its sheen as poverty and inequality, the weight of which is borne disproportionately by Black people, proved stubbornly persistent. Coming of age during this time in a country whose racial inequalities and class disparities were so in your face, I found it increasingly difficult to enjoy Noah’s brand of comedy that treated everyone as fair game. When directed at poor Black people, his jokes felt like they were punching down on people who were already downtrodden. I wondered: were the racial tropes that were the stock and trade of Noah’s jokes subversive, or did they offer audiences a way to justify their own unchecked bigotry? While recognising the paternalism of being offended on behalf of the most marginalized of South Africans, I also felt there was a danger in refusing to interrogate what we were laughing at and why we found it funny.

In his 2012 special, That’s Racist, Noah made his most explicit attempt yet at socio-political commentary. The special was meant to highlight how race still orients, if not corrodes, our perceptions of one another in South Africa. As I watched, I found I’d outgrown his work. Even the skits where Noah’s screwball physicality and masterful accents elicited the kind of hysterics that reminded me why I liked him in the first place could not win me back. More so as these moments were overshadowed by Noah’s ignorance of the historical complexities of the issues that he took pleasure in lampooning.

This was evident in his commentary on the Marikana Massacre, where the police shot dead 34 miners and injured 78 others during an unsanctioned strike in August 2012. The strike came after a breakdown in negotiations between the miners’ aloof union leaders and their employer, the now-defunct platinum producer Lonmin Plc, whose operations have been taken over by Sibanye-Stillwater. The miners, in turn, led by their rank and file, went on strike to demand safer working conditions, improved living quarters, and an increase to bring their monthly wages to 12,500 ZAR (approximately 1,500 USD at the time). The excessive force used by the police, who fired 400 rounds of live ammunition and 500 rubber bullets at the miners, received swift international condemnation, drawing comparisons to the brutal violence of the apartheid regime’s actions during the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 and Soweto Uprisings in 1976.

Yet, instead of being more circumspect, Noah, who was not in the country when the massacre unfolded, insisted that the coverage had been dogged by “sensationalism.” He went on to reduce the miners’ demands to them just “wanting more money” and defended the police’s use of live ammunition, joking that rubber bullets and teargas “don’t work anymore.” With the audience laughing along, Noah added, with a growl punctuating what sounded like a heartfelt rant coded as comedy, “Teargas has just become part of a strike now. It’s like a little smoke machine. It adds ambiance to the atmosphere. You’re wasting your time with teargas!”

It seemingly didn’t occur to Noah that the grievances of the Marikana miners were driven by a need for basics like clean running water, electricity, and sanitation systems compatible with the country’s constitutional promise of human dignity. Their demands for a living wage and improved workplace safety were not unreasonable given the South African mining industry’s long history of poor safety standards and the exploitation of Black workers.

Towards the end of the special, Noah expressed his frustration with the enduring potency of the k-word, a racist anti-black slur that is considered highly offensive in South Africa. So reviled is the word that it was explicitly prohibited in 2000 as a form of racial discrimination and the courts have in recent decades regarded it as hate speech punishable with jail time. Yet Noah insisted that the racial epithet ought to be destigmatised, proposing a “national k-word day,” where South Africans of all races would be given the green light to refer to one another as k-words.

But even if all South Africans were given a free pass to utter the slur, Black South Africans would have to bear the brunt of being called, repeatedly, a word inextricably tied to a painful history of violence and subjugation that has yet to be fully remedied. While Noah’s provocative suggestion may have been his attempt to push the boundaries of his racial comedy, it reiterated the pitfalls of humour that ignores social dynamics in its efforts to treat everyone as fair game. Invariably, it ends up siding with the powerful and making fun of the vulnerable.

That’s Racist was the moment that I stopped seeking out Noah—or so I thought. Even as he made his first waves in the US, appearing on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno in 2012 and on The Late Show with David Letterman in 2013, I didn’t go out of my way to watch him as I once had. In clips that randomly found their way to me through Facebook, I noticed he’d taken his neutral observer shtick nuclear, playing a naive, unassuming (yet world-weary) African in these here United States of America, trying to understand the bewildering customs of this new land. This material would form part of African American (2013), a special that I discovered through a 2015 Grantland essay by cultural critic Wesley Morris, who described it as “70 minutes of condescension and backhanded compliments.”

Out of interest, I decided to watch. If That’s Racist advocated ill-advised ideas at the expense of Black South Africans, then African American was its American equivalent. There are sections so caricatured that they would be considered minstrelsy if Noah wasn’t Black. In one part of the special, he describes his excitement at being read as Black in America, a racial categorization that eluded him back home. Though his tone is facetious, he seems to hold genuine admiration for Black American culture, stating that “there is no cooler Black than American Black.”

Regrettably, the compliment is followed by patronizing remarks around the term “African American,” which he declares a misnomer because Black Americans, supposedly, aren’t really African. He then derides certain Black American names and naming practices, concluding that “it’s almost like they lose their minds with the Scrabble pieces while giving birth.” Finally, he expresses admiration and feigned surprise that Black Americans made “you know what I mean” sound cool by pronouncing it as “na’ mean,” which he added would be what he’d name his daughter if he had one. But contracting words is a normal feature of every spoken language and, as Morris observes, Noah was “trying to get at the way in which Black American culture has taken over pockets of the world. How it has informed his impression of Black Americans. But he never gets out in front of the joke.”

In a GQ profile in 2015, Noah expressed half-regret over the skit. He said that had he known what he knew now, he would have done it differently as he had inadvertently “given some people ammunition to oppress those who had already been oppressed” because he “hadn’t fully understood the African-American experience”. I was relieved to read Noah’s apology, but it seemed he didn’t realise that his everyone-is-fair-game approach was perhaps part of why he hadn’t felt the need to understand the Black American experience before poking fun at it. I also couldn’t help but wonder if he’d ever considered saying sorry for his Marikana Massacre or k-word skits, where he poked fun at Black South Africans—another group with a history of oppression similar to African Americans.

Noah’s unveiling as Jon Stewart’s successor on The Daily Show was contentious and is now part of his personal lore. As he joked on 60 Minutes with Lesley Stahl in 2022, it was a terrible decision initially. “Everybody hated me. People didn’t even know me and they hated the idea of me,” he said.

Having long sworn off Noah’s work, I felt strangely defensive as he faced criticism from American liberals who loved Stewart’s brand of, as writer Jamelle Bouie put it, “left-leaning cynicism (sprinkled with occasional earnestness)”. Their mass mourning over Stewart revealed the extent to which his high-minded snark had become a trademark over his 16 years on The Daily Show. With his relative youth, upbeat demeanour, and wheelhouse of accents, Noah seemed too cheerful, too lowbrow, and foreign, for an audience who had made this virtuous irony part of their identity. Despite Noah’s best efforts, The Daily Show ratings took a plunge and reviews got even more wounding. But Noah kept at it, regardless of how often people told him he’d destroyed the show.

This hostile reception brought to mind a scene in the 2011 documentary You Laugh But It’s True, directed by Noah’s longtime collaborator David Paul Meyer. In one scene, a group of white South African comedians bemoan Noah’s debut performance of The Daywalker, accusing him of arrogance and disrespect for not paying his dues. What they really seem bothered by is the nerve of a young Black comedian reaching for the brass ring instead of kissing theirs. Noah’s response to them was simple: “I’ve heard everything these guys say. I don’t have time for that. I live my life.”

Admittedly, the credibility questions Noah faced on The Daily Show had more legitimacy than the catty gripes he faced on debut in South Africa. In the long run, it was Noah’s resilience that earned him the respect of even viewers who were so determined not to like him. The unsinkable infrastructure of The Daily Show also meant that Noah would never find himself drowning. And his break came, ultimately, with Donald Trump’s presidential run and victory in 2016.

Just a few months before Trump began his term in office, Noah performed a segment likening the former reality TV star to African dictators. It was his most well-received segment since he took over from Stewart. By leaning on the trope of a tyrannical African leader subjecting citizens to outlandish whims, Noah was able to tap into a repertoire he’d honed mocking South African politicians like Malema and Zuma to affirm the traditional Daily Show audiences’ questionable belief that the Trump presidency was an aberration. Noah was also able to once again transpose his impartial bystander status to The Daily Show stage, deploying both his mixed-raced identity and his foreignness (particularly as a person who lived through apartheid) to present himself as a moral conscience in the congested late-night circuit. This treatment of comedy as ethnography, not to mention the inclusion of more global news stories and more diverse correspondents and production staff, won the affection of those looking for a different flavour of political commentary. While The Daily Show’s cable-TV viewers fell by over two-thirds, a widespread trend across the medium, the show under Noah’s reign grew its online platforms and social media channels, attracting a younger, more international demographic who identified with the host’s more cosmopolitan humour.

This treatment of comedy as ethnography, not to mention the inclusion of more global news stories and more diverse correspondents and production staff, won the affection of those looking for a different flavour of political commentary.

But it wasn’t just the egalitarian appeal of comedy that these viewers had gravitated towards. With the publication of his 2016 New York Times-bestselling memoir, Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood, Noah used the story of his upbringing to cast himself as a precocious African kid who triumphed against the odds, marketing himself as the kind of underdog whom Americans could not only root for but relate to. Coupled with his work on Between the Scenes, the Emmy-award-winning after-show web series where he’d take questions from the audience, Noah cut a more sincere figure than his counterparts on the late-night scene. Yet even in these relaxed settings, Noah always seemed “on.” His responses sounded mannered and rehearsed, delivering a perfect allegory and sermon to an audience who treated his every word as gospel.

When the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, Noah handled the transition better than most. In the rebranded The Daily Social Distancing Show, he relaxed into a collection of snug hoodies, and grew out his afro due to lockdown restrictions. His ability to handle this unpredictability helped him navigate the police murder of George Floyd in May 2020. Noah spoke off the cuff about racism in America in a monologue that spanned 20 minutes, lending his support to the uprisings unfolding across the country and the world. Though it wasn’t the first time he’d addressed police brutality on The Daily Show, having condemned the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, he had an intuitive understanding of what to say and how to say it. As a result, Noah joined a host of writers, artists, personalities, and activists whose perspectives on race were highly sought out—so much so that Morris, who doubted him five years earlier, listed Noah among people who could help navigate a televised truth and reconciliation commission for race in America modelled after the South African version, despite criticism of that commission’s ability to deliver justice to the victims of apartheid.

The prestigious hosting gigs and awards that followed capped off a remarkable turnaround, allowing Noah to end his run as the show’s host with his head held high. Looking back reveals how Noah’s success in and beyond the United States was an outcome of having developed his comedic skills in a South Africa in transition. As tastes and sensibilities have shifted to reflect changing perceptions of race, class, and identity, Noah has managed to forge his own ground, achieving mass-market appeal amid the “culture wars” and political climate in both South Africa and the United States. Over a career of notable hits and many misses, he has always sought and often found a new midpoint, using his outsider-insider persona as a gateway to acceptance and consensus among audiences.