The Labour of Solidarity

Through interviews and visual sources, Drew Thompson offers a window into the anti-apartheid strategies of the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement.

Illustration by Mia Coleman

During the 1960s and 1970s, photography was central to a politics of representation adopted by solidarity movements involved in African and African Americans’ freedom struggles. At the same time, photography companies like the Polaroid Corporation understood the financial and branding benefits to recognize both African and African American populations as the consumers and users of its automated colour film products. Popular magazines like Jet in the United States and Drum in South Africa featured advertisements that highlighted the wonder of a person seeing a quality colour photograph in 60 seconds. Advertising mottos included the phrase, “It’s like opening a present.”

These appeals and commercial acknowledgment, however, did not stop Polaroid’s own Black workers from questioning the company’s business at a pivotal moment in history. The period was the height of the civil rights movement in the United States and coincided with a radical shift in the employee demographics at Polaroid. The company’s founder, Edwin Land, a scientist and inventor, had sought to present a progressive image. In the period after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, Polaroid focused on hiring more Black workers, who by 1971 constituted 10 percent of the company’s workforce, in positions ranging from vice president to research scientist to custodian.

Among those who joined the company during this time were Caroline Hunter and Ken Williams. Hunter accepted a job at Polaroid after graduating in 1968 from Xavier University, a historically Black college in Louisiana. The first-generation college graduate and trained chemist worked in Polaroid’s research laboratory dedicated to improving the goop essential to self-developing colour films. According to Hunter, there was the appearance of upward mobility at Polaroid, but the workplace still felt segregated. Hunter met Williams on a Polaroid-sponsored community mentorship program in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Later, they would become a couple.

Hunter and Williams met for lunch one day in late 1970. On their way out of the building they passed a flyer that featured an ID card and referenced Polaroid’s business in South Africa, which was not previously disclosed to them. That evening, or later that same week, they visited a library to do more research. They confirmed their suspicions: South Africa’s apartheid regime was using Polaroid cameras and films to issue passbooks.

They confirmed their suspicions: South Africa’s apartheid regime was using Polaroid cameras and films to issue passbooks.

First introduced in the seventeenth century during Dutch colonialism in the Cape, this internal passport system served to control the movement of Black South Africans over the age of sixteen. After 1948, the nationalist apartheid government ruthlessly implemented the system. Each passbook contained personal details about the carrier, including a headshot, their fingerprints, address and employer’s name (without whose signature they weren’t allowed in a “white” area, which meant most of South Africa, for longer than 72 hours). By 1970, a fair number of Black South Africans in jail were there for pass offences. For example, a 1971 New York Times article under the headline “South Africa to Ease Penalties for Passbook Infractions by Blacks” reported that half of South Africa’s prison populations, approximately 44,000 people, were jailed for violation of pass laws. The article also quoted a South African police report that claimed over 900,000 non-white South Africans, in particular Blacks and Coloureds, had faced prosecutions over pass law offences.

Hunter’s own introduction to apartheid and South African history had come in tenth grade when she read Alan Paton’s 1948 novel, Cry the Beloved Country. She likened growing up in the South under segregation to “America’s apartheid” and recalls the outrage she felt when first becoming aware of Polaroid’s South African business. Making a connection to the company’s late 1960s advertising campaigns, she said, “Excitement and joy bound people to their death.”

Hunter and Williams co-founded the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement (PRWM) believing that the Polaroid Corporation contributed to racial injustices experienced by Black South Africans. They had the explicit aim of forcing the company to acknowledge its involvement in apartheid. In Hunter’s thinking, an aggressive and clear strategy was required to challenge the well-resourced and highly connected Polaroid Corporation. The PRWM quickly set out to raise public awareness by posting flyers at employee entrances and inside break rooms throughout company headquarters. One of the group’s slogans that appeared on the printed flyers was “Polaroid imprisons Black people in just 60 seconds.” Through this pithy phrase, the group wanted to present the popular colour film technology as a tool of imprisonment, responsible for racial segregation and white-minority rule in South Africa.

I first became interested in Polaroid’s business in Africa while researching the use of photography in Mozambique’s liberation struggle, and the process of decolonization that followed independence in 1975. I frequently encountered Polaroid advertisements in Mozambique’s colonial-era newspapers from the 1960s and 1970s. Interviews with commercial studio owners and photojournalists suggest that Polaroids were not widely used or important. There was no mention of the PRWM within anti-colonial circles in Mozambique or the liberation movement Frente da Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO). However, activists in the United States affiliated with Southern African freedom struggles did reference the PRWM and speak out on the movement’s behalf. There existed in the early 1970s in particular a certain awareness of an anti-apartheid activist movement centred on Polaroid’s business in South Africa that pointed to a connection between the development of instant photography and surveillance.

I sought out Caroline Hunter to learn more about this history and the impact of PRWM. We met finally in the spring of 2023 and visited the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The Schomburg, as it is known, is in the New York City neighbourhood of Harlem and is one of the leading research centres of primary source materials on Black culture and history in the United States. There, we located a series of PRWM-produced flyers in a file archived under the “Southern African Collective.”

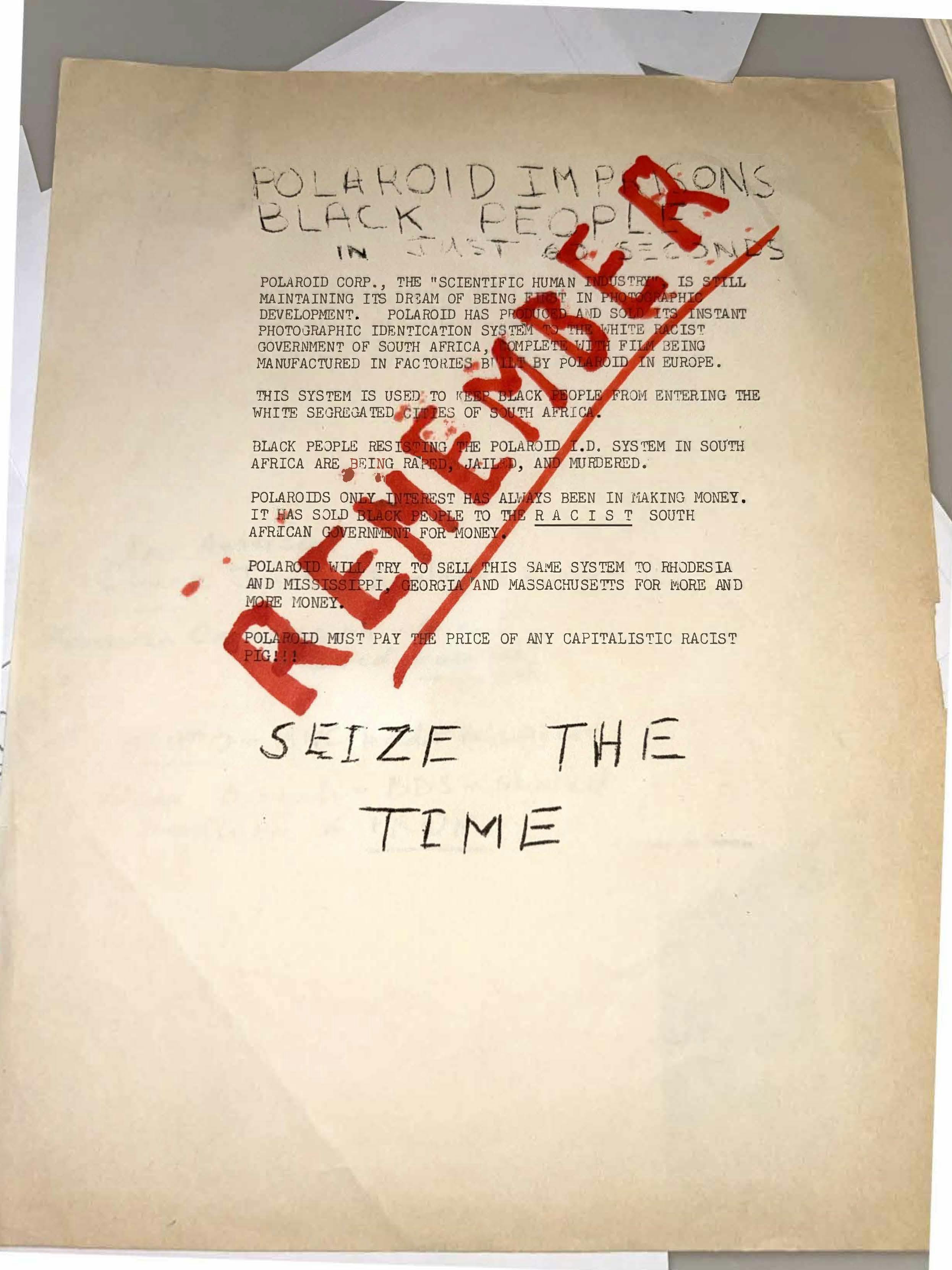

We found a copy of the “Polaroid Imprisons Black People in Just 60 Seconds” flyer. Looking at the 8½ × 11-inch copy paper, I noticed that typed and handwritten text featured prominently as opposed to images and graphics. The first third of the typed text, organized in short paragraphs, claimed that Polaroid used the labour and ingenuity of its workers to build equipment sold to aid segregation in South Africa. It also highlighted efforts to sell equipment for similar purposes to Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe), which was north of South Africa and another country under white-minority rule. Finally, the poster mentioned Polaroid’s use by state governments in the US. Centred at the end of the text was the handwritten phrase “SEIZE THE TIME,” a popular slogan associated with the Black Panthers activist group and also the title of a 1970 book by Bobby Seale, one of the group’s leaders. Handwritten in red permanent marker and resembling dripping blood, the word “REMEMBER” crosses out the typed and handwritten text. Nowhere does the PRWM’s name appear.

PRWM leaflet calling attention to Polaroid’s complicity in apartheid South Africa (Source: Drew Thompson)

The flyer displays material elements—ink residue and photocopy effects—that speak to its circulation and repurposing. As Hunter explained, the PRWM was an exercise in coalition-building, and flyers connected the organization with different people across the globe. The PRWM had a shoestring budget and no front office, she said, meaning Hunter and Williams sometimes made flyers at home after work and used company materials. There was no precise reasoning for what text was handwritten or typed. Nevertheless, flyers were an important mode of communication precisely because they afforded a space to add individualised commentary. Recipients could use typewriters or handwriting to reproduce flyers’ contents and duplicate them independently of the PRWM.

Another flyer dated October 23, 1970, listed the group’s demands. The PRWM requested Polaroid to publicly acknowledge its clandestine business in South Africa and to use funds obtained through divestiture to aid African freedom struggles. On the same flyer, Williams wrote to explain that the Polaroid Corporation had not responded to the PRWM’s demands.

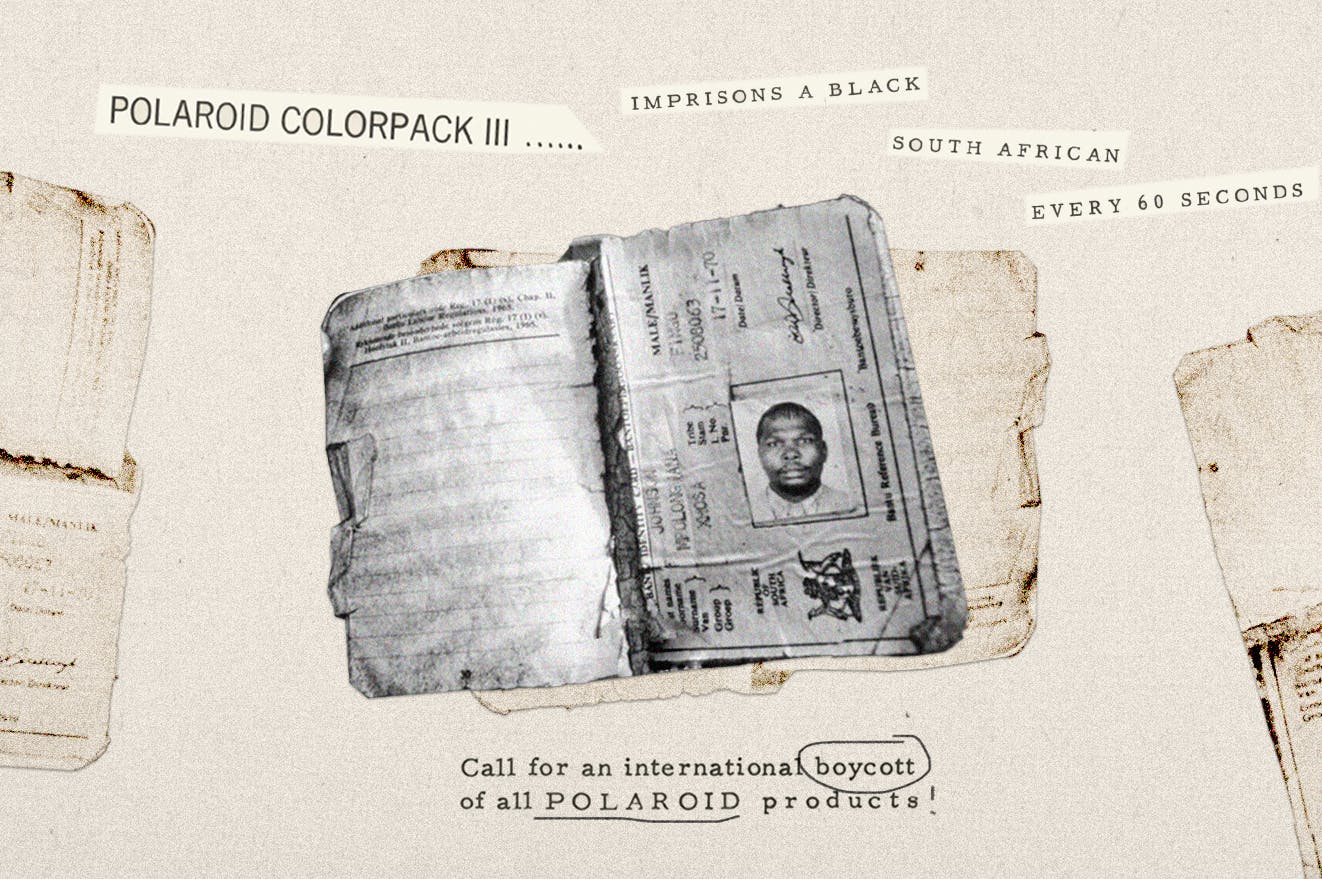

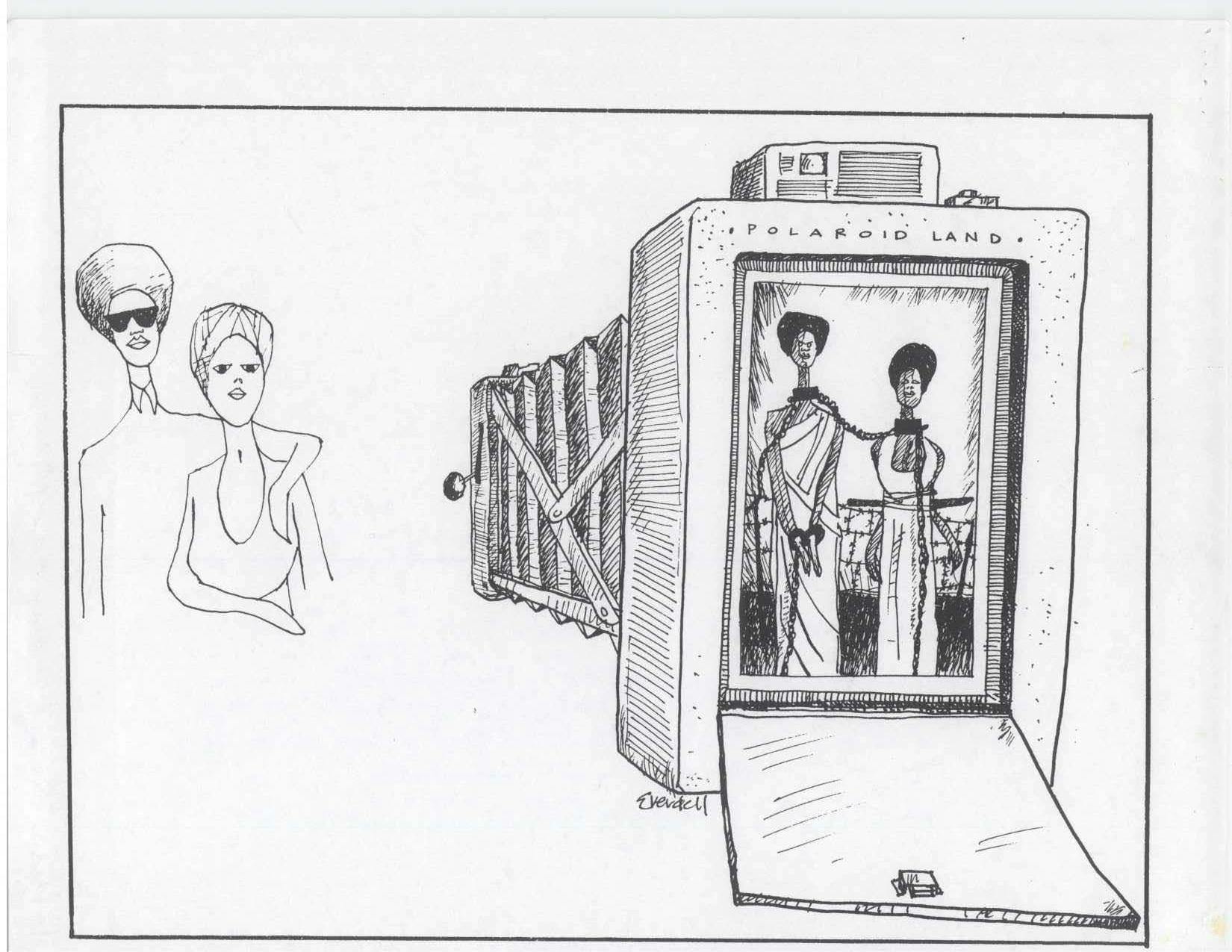

As a sign of the campaign’s burgeoning traction, the PRWM demands later appeared word-for-word in newsletters printed by the University Christian Movement, the Southern African Committee, and the Madison Area Committee on Southern Africa, all groups that organized against apartheid in South Africa. These groups accompanied their reproduction of the text provided by the PRWM with imagery. In one instance, a newsletter printed by the Madison Area Committee on Southern Africa at the University of Wisconsin featured a graphic of a placard with the text “Polaroid and South Africa/Partners in Racism/Boycott ‘Em Both” and an image of a raised clenched fist, the internationally recognized symbol of freedom and struggle. Other graphics included a drawing where two people posed in front of a Polaroid camera, with the camera’s film compartment featuring the same people chained together, so as to suggest Polaroid’s complicity in conditions of incarceration.

Another flyer by the PRWM from early 1971 (Source: African Activist Archive, Private Collection of Caroline Hunter)

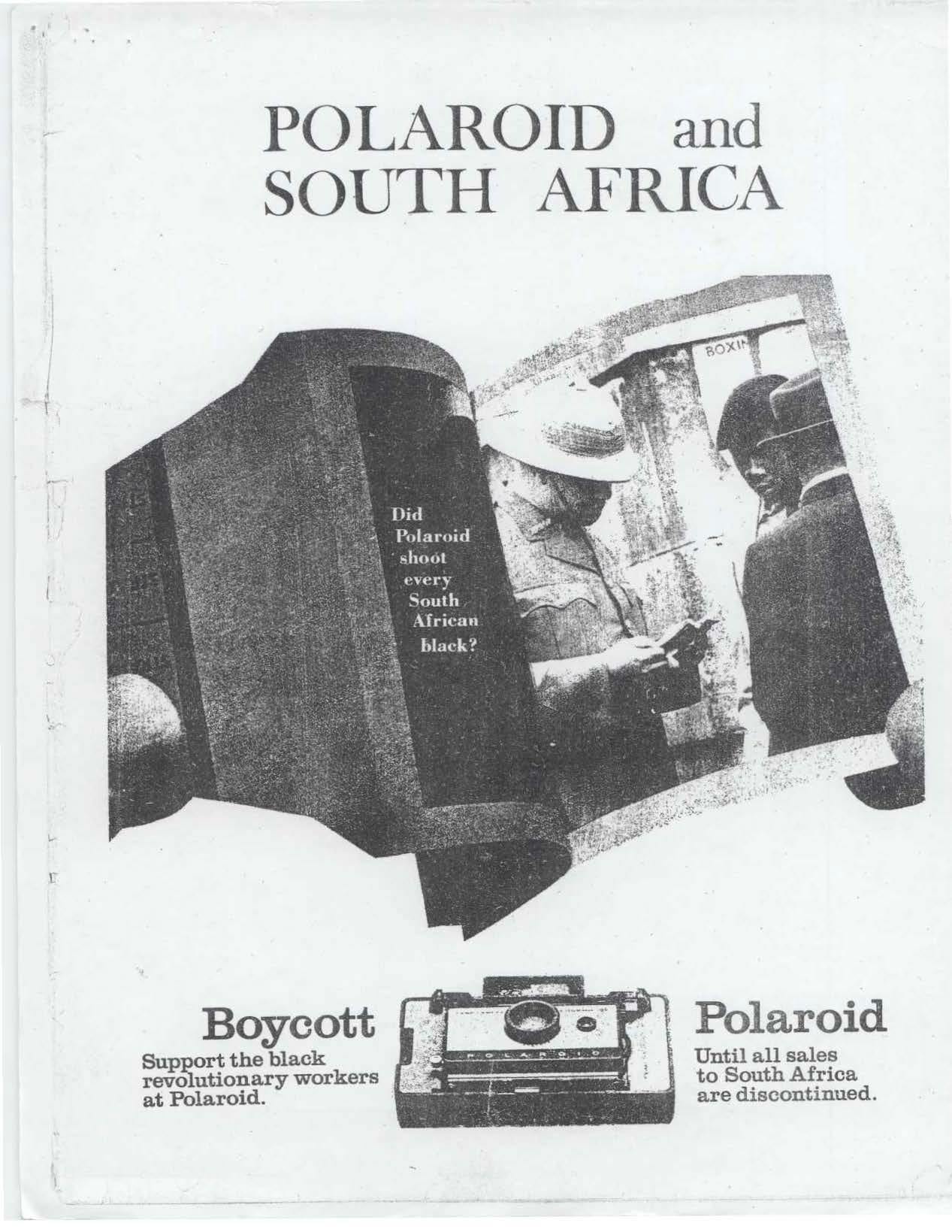

Text-based flyers circulated widely, and in the process helped to elevate public awareness of the PRWM. One of the sleekest and most professionally done of these flyers appeared months into PRWM’s activities and featured the words “Polaroid and South Africa.” Below the text was an image of fingertips pulling a Polaroid photo from its negative—a step critical at the time to using the company’s self-developing films. Alongside it appeared an image of a white police officer inspecting the passbook of two Black men. On the side of the negative appeared the text, “Did Polaroid shoot every South African black?” Underneath the image in some versions of the flyer was the phrase, “It’s like opening a present.” At the bottom of the page was text printed in a font and layout that mimicked Polaroid’s magazine’s advertisements, possibly to draw a connection between recreational and bureaucratic uses of Polaroids. Here the text ultimately encouraged consumers to boycott Polaroid and support the PRWM until the company ended its business in South Africa. The Polaroid photo in the flyer resembled the photographs of police inspections of passbooks taken by Black South African documentary photographers of the time such as Ernest Cole and Peter Magubane. The photo was intended to reference the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre outside Johannesburg, which resulted in the police killing of people who gathered to protest pass laws.

Flyer by the PRWM from early 1971 (Source: African Activist Archive, Private Collection of Caroline Hunter)

The flyer was of great significance for PRWM. It offered a means to link the recreational use of Polaroid’s products to apartheid in South Africa. It also played on Polaroid’s advertisements so well that it could easily have been mistaken for a magazine advertisement. And at this moment, the PRWM’s own image-making capabilities rapidly expanded.

Explaining how the PRWM produced the flyer, Hunter said that “really, professional allies [in] London” had done it. She did not have any details about how this relationship with a far-flung ally came about. One is left to conclude that perhaps the group became aware of the PRWM through a flyer that circulated secondhand and wanted to contribute to advancing its efforts by creating a professional-looking document.

There was a personal cost to solidarity. Shortly after the PRWM’s founding in 1970, Polaroid fired Williams. Then in early 1971, Hunter faced termination. In response to the PRWM’s actions as well as to clarify its business in South Africa, Polaroid produced a host of public relations materials, including internal memoranda sent directly to Williams and Hunter as well as those distributed throughout the company. Hunter and Williams collected these materials, regularly incorporating cut-out corporate logos or text from internal correspondences sent by Polaroid leadership and reproduced them in flyers and pamphlets. In one instance, Hunter published her termination letter in a pamphlet printed in conjunction with the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based African Research Group, which included other newspaper articles and graphic commentary.

Reusing phrases and logos from Polaroid’s magazine advertisements and other company materials allowed the PRWM to use the corporation’s marketing against them. These actions put Polaroid in a position where it felt compelled “to counter, to say [what was] not true,” Hunter said. Polaroid was drawn into “fact-checking,” she added, and the company was forced to clarify and defend its own actions while allowing the PRWM to highlight certain inconsistencies and hypocrisies in policy and rhetoric.

Polaroid could avoid the PRWM for a while because the group lacked specific proof of Polaroid’s business in South Africa. For example, upon learning of the PRWM’s demands, Polaroid explained that a third party, Frank & Hirsch, sold its products in South Africa and that the company could not be held responsible for how people used them. The company did not account for how their products fell into the hands of apartheid government officials and were used to restrict Black people’s freedom of movement. To compensate for the lack of specific visual and textual documentary evidence and rhetorical ambiguities, PRWM members and supporters upped the production of pamphlets and other materials. Quickly, these interventions evolved to include photographs of PRWM protest gatherings and events unfolding in South Africa.

The strategy worked. A person familiar with Polaroid’s corporate response would later recall that while Polaroid had no subsidiary or staff in South Africa and the profits there were relatively small (300,000 USD per year), Hunter and Williams’s efforts garnered sufficient negative press in American mainstream media for Polaroid to respond.

In 1977, the Polaroid Corporation ceased doing business in South Africa.

Internationally, sanctions against South Africa had become commonplace, and the PRWM especially resonated with anti-apartheid activists based in the United States, many of whom were Black. Historically, many Black Americans had organized themselves in solidarity with Southern African liberation movements, sometimes traveling to the region to lend technical and humanitarian support.

One example is the attorney-turned-filmmaker Robert Van Lierop, who first became aware of the PRWM through Black student activists at Dartmouth College. Van Lierop would write to Polaroid’s chairman, Edwin Land, in support of the PRWM and demand that the company close its operations in South Africa. He continued his letter writing campaign in early 1971, the same year he travelled to Tanzania and Mozambique. There, he and two other people photographed and filmed daily life inside FRELIMO’s liberated zones, managing to document an air raid conducted by the Portuguese military—images pivotal to FRELIMO’s claims of legitimacy and Mozambique’s independence. Van Lierop compiled the footage into the 1972 documentary film A Luta Continua. While and after filming, Van Lierop faced FBI surveillance. He later met Hunter and Williams when they testified on behalf of the PRWM at the United Nations.

Prexy Nesbitt was an associate of Van Lierop and is another example of the reach and impact of the PRWM among Black Americans involved in Southern Africa’s liberation movements. Originally from Chicago, where he once served as part of Martin Luther King Jr.’s security detail during a march in the early 1960s, Nesbitt went on to study in Tanzania, where he met Mozambican exiles. He helped to edit FRELIMO’s magazine publication, Mozambique Revolution, and tutored women and children affiliated with the struggle in Tanzania, which is how he came to the attention of Black American media like Jet.

In coverage on the standoff between PRWM and Polaroid, Jet, like most American media, had reported the company’s perspective, citing company documents and leadership. Nevertheless, in an article carried in the magazine on December 10, 1970, on Polaroid’s collusion with apartheid South Africa, Nesbitt (by then an official of the American Committee on Africa) is featured prominently commenting on police checks and failings associated with passbooks in South Africa. Nesbitt called out Polaroid by name. “Polaroid’s sale of the I.D. 2 system to South Africa is one clear example of how American companies support the oppression of Black people in South Africa,” he said.

Passbooks were eventually abolished in South Africa in 1986. By then, tens of millions Black South Africans had been arrested for breaking pass laws.

Now, 30 years after the formal end of apartheid, PRWM is credited with being one of the first anti-apartheid boycott efforts in the United States to target US corporations. During a recent exchange, I asked Hunter to comment on PRWM’s impact on anti-apartheid efforts in the United States. She mentioned Van Lierop and George Houser, the founder of the American Committee on Africa. She also said, “I think, for a lot of people who were anti-apartheid activists before we discovered the I.D.[-2 system] at Polaroid, we were a breath of fresh air. Prior to that, it was an intellectual conversation about what people wanted to do. A lot of mobilization in Europe and around the world … They were all excited about our entry into the fight.”

A closer look at the materials produced by the PRWM and allies of the group highlights what amounted to the labour of solidarity, visual strategies crafted and cultivated in the absence of photographic sources. Such responses led other sympathetic groups to craft their own imagery. As Hunter observed, “Solidarity can be built around common issues.”