The Inescapable Single Garment of Destiny

Three decades since the fall of apartheid, with much still to be done to fulfil the promise freedom for all, Robert Trent Vinson revisits the historical ties between Black South Africans and African Americans

Illustration by Mia Coleman

In 1891, six young South Africans, including one Charlotte Mannya, established the African Native Choir, modelled on the Virginia Jubilee Singers, an African-American theatrical troupe of formerly enslaved people who toured South Africa from 1890. The African Native Choir went on to tour England and the United States, hoping to raise funds for a technical school in their home country. While on tour in the US, they met Bishop William B. Derrick of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, who arranged for some of the group, Mannya among them, to enrol at Wilberforce University, Ohio, a school run by the AME church.

From Wilberforce, Mannya wrote home about her life among formally educated Black people who seemed to enjoy a high degree of self-determination. Her uncle, Mangena Mokone, read the letters and, in admiration, began exchanging letters with the leadership of the AME church, in particular Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, who later visited South Africa. Mokone had at the time been among several prominent Black Christians who left racially inequitable, white-led missions to create their own independent, Black-led churches in South Africa. Congregants of these churches identified with “Ethiopianism,” a theological framework that considered biblical Ethiopia a synonym for Africa and a historical site of an ancient Black Christian nation. Ethiopianists interpreted Psalm 68:31—“Princes shall come out of Egypt; and Ethiopia shall stretch forth her hands unto God”—as a prophecy that Africans would regain their independence. Their ideas were amplified when, in 1896, Ethiopia defeated Italy and maintained its independence, even as European powers colonised the rest of Africa.

Mokone and Turner’s correspondence blossomed into a full-fledged partnership that saw African-American missionaries from the AME and the National Baptist Convention establish still-existing, Black-led churches and schools in South Africa. Those churches also became conduits for the education of over a few hundred Black South Africans in American universities between 1895 and 1940. In 1903, Mannya herself, better known by her married name Maxeke, graduated from Wilberforce, becoming the first Black South African woman to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Members of The African Native Choir, including Charlotte Mannya (second from the right, middle row) pose for a group portrait, 1891. (Source: Getty Images)

The stories of Mannya, her band members, and fellow graduates who came through AME churches and schools point to the long history between Black South Africans and Black Americans. It is no coincidence. South Africa and the United States have broadly similar historical trajectories of racial subordination, beginning with the seventeenth-century arrival of European settlers, the subsequent conquest and land dispossession of Indigenous peoples, and then centuries of slavery and post-slavery societies marked by political disenfranchisement, economic exploitation, and justifying ideologies of Black inferiority. In the twentieth century, white government officials of both countries pointed to these broadly similar histories to claim a shared sense of identification with each other, particularly to justify their Cold War-era alliance. But for African Americans and Black South Africans, these broadly similar histories reflected what W.E.B. Du Bois, who taught at Wilberforce in Mannya’s time, called the problem of the “global colour line.” The mutual intelligibility of the two contexts created opportunities to seek solutions to this problem through transnational exchanges and solidarities in political, religious, educational, economic, and sporting arenas. These relationships were part of networks within and beyond South Africa’s borders that propelled the movement against apartheid, contributing to its ultimate toppling.

Today, as South Africa marks 30 years of democracy amid ongoing struggles for racial equality, it is worth revisiting the century-long shared struggle and solidarities between Black South Africans and Black Americans. Having written extensively on the topic, I am curious about how Black Americans drew on their proximity to the heart of empire, among other strategies, in support of the struggle for Black liberation in South Africa. I am curious, too, about what can be learned from the limits of this strategy inherent in its reliance, for its efficacy, on hierarchies, power imbalances, and logics it sought to challenge. As the past shows, this dynamic is not without its frictions.

Having written extensively on the topic, I am curious about how Black Americans drew on their proximity to the heart of empire, among other strategies, in support of the struggle for Black liberation in South Africa.

The African-American presence in southern Africa began as early as the 1780s, with a small trickle of sailors, traders, and adventurers. In July 1863, during the American Civil War, the Confederate warship Alabama, infamous for its raids on merchant ships on both sides of the Atlantic, docked in Cape Town with David White, a captive Black man, aboard. While we know nothing of White’s possible interactions with local communities, we do know that the Alabama spent more time in Cape Town-area ports than in any other port in the world. It was reputedly memorialised in the still-popular Afrikaans song “Daar Kom die Alibama!” (There comes the Alabama!).

Performances of the touring Virginia Jubilee Singers emerged as another context for relationships between African Americans and Black South Africans. Between 1890 and 1898, the group performed about a thousand wildly popular concerts across South Africa, laying the groundwork for trans-Atlantic racial solidarities against accelerating European colonial conquest in Africa and American Jim Crow. The group’s charismatic leader, Orpheus McAdoo, often began concerts by narrating an “up from slavery” history of African-American progress, from 246 years of slavery to post-Civil War freedom and achievement despite continued white American intransigence. The concerts featured hauntingly rendered spirituals like “Let My People Go,” exemplifying prophecies of liberation that cast formerly enslaved African Americans as modern-day biblical Israelites: enslaved but ultimately liberated from Pharaonic Egypt.

In the period before 1940, solidarity between Black South Africans and African Americans was grounded in these narratives of inevitable progress, alongside religious ideas of Ethiopianism and of “providential design”—beliefs that God had divinely ordained African Americans to be models of racial advancement and agents of potential liberation to colonised Africans. Upon hearing stories of elected African-American politicians and Black church and educational institution-building in post-Civil War America, admiring South Africans such as Josiah Semouse, a member of the African Choir, inserted themselves into African-American narratives, asking, “When will the day come when the African people will be like the Americans? When will they stop being slaves and become nations with their own government?”

But while McAdoo’s pre-concert narration rightly pointed to African-American achievement after the American Civil War, it did not adequately convey the realities of American Jim Crow, which would reverse many of those gains, consigning African Americans to the status of second-class citizens, laying ground for the American Civil Rights Movement decades later.

Ironically, as African Americans were losing full citizenship rights in America, the Virginia Jubilee Singers successfully appealed to American diplomats to intervene on their behalf to South Africa’s authorities, to assert that their American citizenship should exempt them from the segregationist laws that subordinated Black South Africans. Thus, they gained “honorary whites” status in South Africa. Some Africans, particularly African Christian elites, who saw their religion and schooling as a means to freedoms reserved for whites, regarded this status as the authorities’ tacit acknowledgement that Black Americans, only a generation out of slavery but with the key attributes of Christianity and education, were fully “civilised” and thus equal under the law. Perhaps then, African Americans exposed the colonial lie that, because of supposed racial inferiority, it would take two thousand years for Africans to be “civilised” enough to regain their precolonial independence.

Alongside arts and religion, education proved to be a crucial site for the cultivation and expression of solidarities between Black South Africans and Black Americans.

In the late nineteenth century, famed African-American educator, writer, and orator Booker T. Washington was perhaps the most significant model of Black self-determination in the development of educational institutions in the United States. In 1881, the formerly enslaved Washington became founding president of the renowned Tuskegee Institute, which boasted an all-Black staff and faculty of three hundred, and a similarly all-Black student body of roughly fifteen hundred.

South Africans like future African National Congress presidents John Dube and Pixley Seme, the ANC Secretary-General Sol Plaatje, and educator D.D.T. Jabavu visited Tuskegee. They became virtual disciples of Washington and the school, with Plaatje showing films of Tuskegee throughout South Africa.

The young John Dube would, in particular, take great inspiration from Washington and emerge an important figure in education in Black South Africa. Born in 1871 during British colonial rule in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, Dube, who came through the religious and educational networks of the American Board of Foreign Commissioners, first arrived in the United States in 1887 to attend Oberlin College. After returning to Natal in 1890, he and his wife, Nokutela, returned to the US and settled in Brooklyn in 1896 to raise funds for a South African Tuskegee. During those years, Dube journeyed to Alabama to see Washington and delivered a commencement speech at Tuskegee, further deepening exchanges between the two men.

In 1900, Dube wrote an essay, “A Zulu’s Message to Afro-Americans,” imploring African Americans to go to Africa to regenerate the continent: “God has wonderfully prepared the Afro-Americans, through years of bondage by a civilised nation (even as were the Jews) for the task of civilising their African brethren, a necessary first step to regain their independence,” he wrote. Fittingly, the letterhead was the seal of Ethiopia, identifying Dube with the Ethiopianist cause. Yet, Dube’s rapturous remarks also reveal the corrosive “civilizationist” assumptions that could appear in these transnational solidarities. In this discourse, God had mandated that “uncivilised” Africans be forced to leave “the Dark Continent” to be “civilised” in the harsh school of slavery in foreign lands as a necessary precursor to bringing the “light of civilisation” to their ancestral continent. South Africa’s mission-educated elite, of which Dube was a primary spokesperson, in turn internalised these beliefs, seeing education and Christianity as key to their liberation.

So it was that the Dubes, upon returning to South Africa in 1900 and with Washington’s encouragement, founded the Ohlange Institute, a school modelled after Tuskeegee. With a Black cosmopolitan leadership, the school featured John as principal, Nokutela as head of the music department, and an all-Black staff, including Reynolds Scott, a Tuskegee-educated man from the West Indies, and two African-American women, Julia Cele and Katherine Blackburn. Earlier, while living in Brooklyn, the Dubes had also facilitated the American arrival of their cousin, Pixley Seme, who eventually graduated from Columbia University in 1906 and won the Curtis Medal, the university’s top oratorical prize, with his speech, “The Regeneration of Africa.” Seme’s speech, a stirring example of incipient African nationalism, positioned the continent at the turn of the twentieth century as “a new and unique civilization … soon to be added to the world.”

Upon his own return to South Africa, Seme helped establish the South African Native National Congress in 1912, with Dube as its first president. The SANNC, a predecessor to the ANC, would later conclude that even though education and Christianity were important, it was only politics that would remove the barriers to advancement, laying ground for what would become a leading anti-apartheid organization, South Africa’s current governing party, and the oldest political party in Africa.

The Universal Negro Improvement Association, the largest and most widespread Black movement in world history, was another source for the exchanges and solidarities. Co-founded in Jamaica in 1914 by Amy Ashwood and her future husband, Marcus Garvey, the UNIA boasted an estimated two million members and sympathizers and more than a thousand chapters in forty-three countries and territories. Through its “Africa for the Africans” militancy, the organisation galvanised millions with its ambitious Pan-African agenda: shipping lines, corporations, and universities; a troubled Liberian colonization scheme; a resolute desire to reconstitute African independence; and a fierce racial pride.

Outside of North America and the Caribbean, these aims and ideals, generically called Garveyism, had their greatest impact in South Africa, with more than a dozen official and unofficial South African UNIA chapters formed. A combination of Black sailors, ships, and newspapers—the era’s most effective means of pan-African communication—transmitted Garveyism into South Africa, and Black Americans in South Africa, mostly those of West Indian descent, established local UNIA divisions. The latter were also prominent in the leadership of Industrial and Commercial Workers Union of Africa, South Africa’s first major Black trade union.

Like many of their contemporaries, Garveyites in South Africa expressed their liberationist aspirations and political grievances grounded in a nineteenth-century prophetic Christianity, including providential design. In this strand of thought, the agents of African liberation were the “15,000,000 negroes of America who have to-day reached the highest scientific attainments in the world,” as one William Jackson, a Jamaican native who served as president of the UNIA chapter in Cape Town, said. Ultimately, perhaps for this fact of framing Black liberation in South Africa as external in origin, Garveyism did not lead to deliverance. However, its ethos and ideals were echoed in subsequent, arguably more impactful political groupings such as the Pan-Africanist Congress of Robert Sobukwe and Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement.

The period after May 1948, when South Africa’s National Party secured an unexpected electoral victory, ushered in a new period of organised resistance within and beyond South Africa, as the party began translating its racist electoral slogans into a comprehensive political program to ensure ethnic Afrikaner advancement and white racial hegemony. Amid this, sport emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a critical arena, though not without tensions among those involved in the anti-apartheid movement, as the story of tennis champion Arthur Ashe illustrates.

Ashe was one of many African American athletes and activists who successfully petitioned to prevent South Africa from participating in the 1968 Olympics. Born in 1943 in Richmond, Virginia, the former Confederacy capital, Ashe had lived through Jim Crow conditions that primed him for civil rights and anti-apartheid activism. Subscribing to the nonviolence of Martin Luther King Jr., who wrote directly to Ashe encouraging his increasing activism, and crossing paths with civil rights activists Andrew Young and Jesse Jackson, the tennis star vowed to “advance materially this whole human rights struggle.”

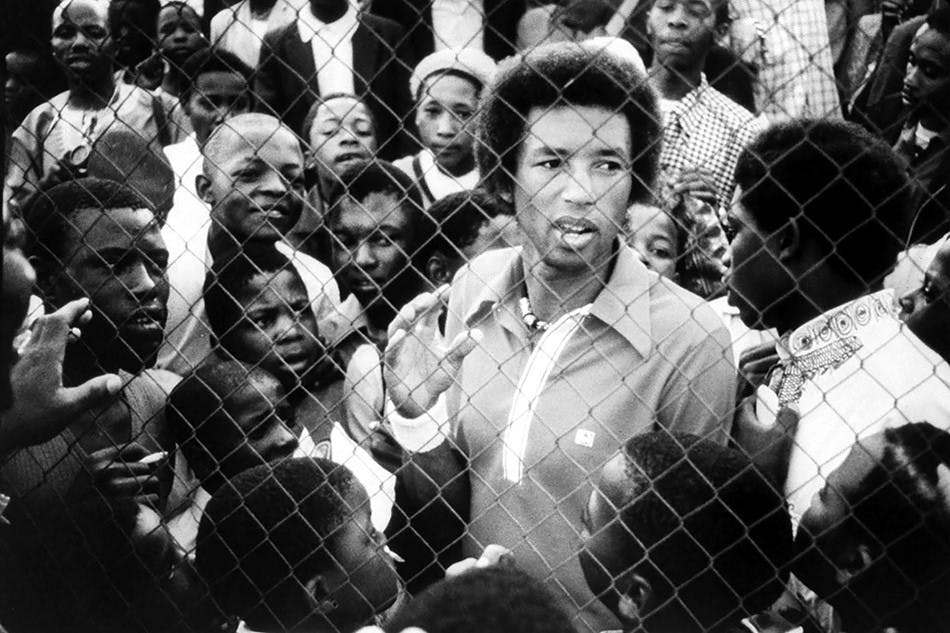

In the 1970s, Ashe successfully lobbied to enter South Africa to compete several times in the South African Open tennis tournament. He hoped to establish direct contact with Black South Africans, gain firsthand knowledge, and amplify global pressure against apartheid. Ashe’s presence generated divergent opinions among Black South African anti-apartheid activists about whether he had helped or hindered the cause. Dennis Brutus, who led the ultimately successful campaign to ban South Africa from the Olympics, Black Consciousness Movement activists in South Africa, and exiled South African students back in America told Ashe personally that he had betrayed the cause. Others like Winnie Mandela, writer Don Mattera, and choral music leader Khabi Mngoma supported his desire to witness apartheid first-hand to more effectively publicise its horrors to the world. Eventually, particularly after the 1976 Soweto uprisings, Ashe concluded that global political isolation and economic sanctions were the best means to support the intensifying domestic South African anti-apartheid struggle.

Arthur Ashe in Soweto (Source: Gerry Cranham/Getty Images)

The 1980s brought with them an increasingly fierce domestic South African insurgency and a burgeoning global anti-apartheid movement that spanned multiple continents. As a part of this, Ashe and civil rights veterans such as Coretta Scott King, Jesse Jackson, Harry Belafonte, and Rosa Parks used classic civil rights-era strategies of marching, picketing, courting arrest, and attracting media attention to advance the anti-apartheid movement. Drawing inspiration from South African political figures like 1984 Nobel laureate Desmond Tutu and Winnie Mandela, Ashe, along with veteran Black activists Gay McDougall, Cecelie Counts, Sylvia Hill, Adwoa Mouton-Dunn, and congressmen Ron Dellums and Mickey Leland, were leaders in the Free South Africa Movement, the longest-running civil disobedience campaign in US history. Ashe, together with Belafonte, co-founded Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid in 1983 and was arrested in 1985 in front of the South African Embassy for protesting apartheid. Ashe also convinced tennis star John McEnroe not to play in a million dollar exhibition in South Africa and urged all other athletes not to compete in the country.

Ashe’s activism was not without personal cost. His anti-apartheid activism discomfited United States Tennis Association leaders who, despite his winning two titles as the country’s Davis Cup captain, forced him out of the captaincy in 1985. Undeterred, Ashe teamed up in 1989 with black South African exile Mark Mathabane in campaigns to maintain sporting bans against South Africa.

As a boy, Mathabane had shadowed Ashe fifteen years earlier as the tennis star moved around Johannesburg’s Ellis Park. To Ashe’s query about why he was following him, the boy replied, “Because you are the first one I have ever seen.” “The first what?” a confused Ashe asked. “The first truly free Black man I have ever seen.” Mathabane earned a tennis scholarship in America and became the author of the best-selling 1986 memoir Kaffir Boy, a compelling firsthand account of apartheid South Africa.

Meanwhile, Ashe became close to Nelson Mandela, who, while still in prison, had felt Ashe’s South African visits were inspirational to Black people and had read A Hard Road to Glory, Ashe’s history of African American athletes. When asked by a reporter before his 1990 visit to America whom he most wanted to see, Mandela replied, “Arthur Ashe.” The two met in the US and in South Africa, and their personal relationship was a poignant example of the enduring transnational connections between black South Africans and African Americans.

In 1994, a year after Ashe’s death, Mandela, a Nobel laureate, gave a symbolic nod to the historical ties that bind African Americans and Black South Africans. He insisted that African American anti-apartheid lawyer-activist Gay McDougall be the official international observer to witness his first-ever vote during the historic 1994 elections. Mandela and fellow ANC luminary Walter Sisulu also acknowledged the deep investment that many African Americans felt toward South Africa and encouraged them to “come home” to help build a post-apartheid South Africa. Like Ghana, Tanzania, and Ethiopia for earlier generations, South Africa could be their chosen site of return to the African continent, away from the corrosive systemic racism of the US.

Indeed, African Americans and Black South Africans up to that moment had journeyed a long road together in hopes of solving the problem of the global colour line, recognising that each specific national struggle is tied inextricably to what Martin Luther King Jr. called a “single garment of destiny.” Today, exchanges between Black people in both countries continue, as do struggles for racial justice and equality—suggesting that this long journey of mutuality and solidarity is bound to continue.