Drawing Memory into Being (2023)

Amid fading memories and enduring legacies of apartheid-era forced removals, this installation seeks to reclaim agency through memory.

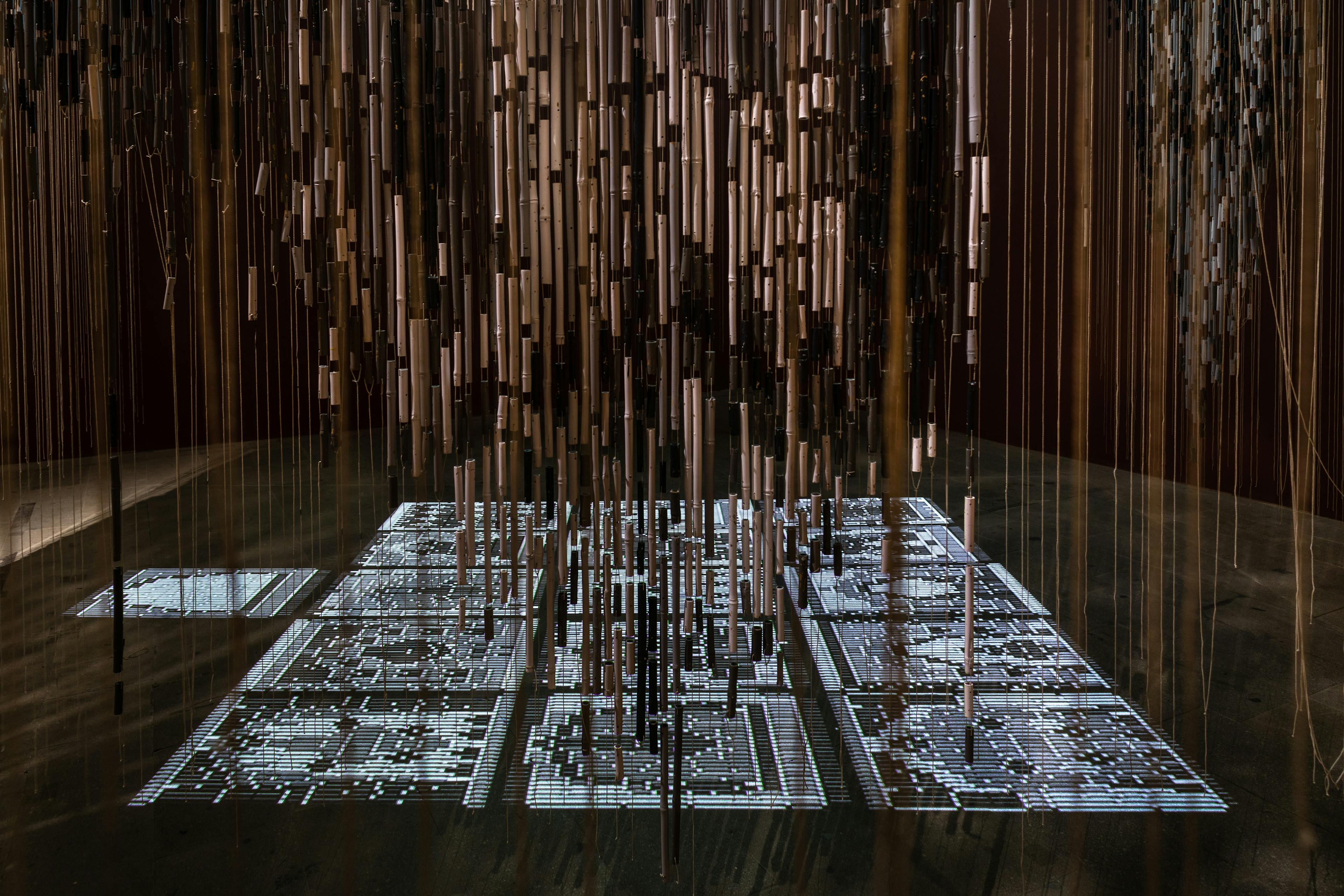

“Created for the eighteenth International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale, ‘Drawing Memory into Being’ was an installation about the relationship between material erasure and historical forgetting. It featured projections of black and white images that tell the story of Malay Camp, a community in Kimberly, South Africa that was forcibly removed and whose homes were destroyed by both the Colonial and the apartheid state from the 1940s. By 1960, all of Malay Camp, a thriving urbanity and diverse community of mainly people of colour, many of whom were descendants of enslaved and free Muslims, had been erased and overwritten.

Newspaper photos provide some of the only remaining evidence of the destroyed mosques of Malay Camp. Over the years, these images have seen multiple reproductions resulting in reduced quality and detail. The diminished images reflect the fading memory of the forced removals and inspired us to create a ghostly and evocative installation of the erased buildings—drawing memory into being.

The installation took the form of a ghostly ruin, broken and made of fragments. We created it using bamboo-beaded curtains, which allowed for a dematerialisation and ghostly evocation each time wind rustled and visitors walked through. We inverted the images of Malay Camp, placing the ground plane above, and inscribed the grid of a musallah, a prayer mat, which served as the architecture of the installation. The musallah and the entire installation faced Mecca. Importantly, the musallah functions without boundaries. It represents the worshipper praying on the grass, nomadic, diasporic. It is about a network of community, smooth space in opposition to the striated space of unjust laws marked by walls and demarcated plots.

This inversion of ground as ceiling was symbolic of the fact that though the buildings no longer exist, the ground remains potent with the performance of prayer and protest. Indeed, today, the erased site of a mosque that once stood in Malay Camp is still used for open prayer. This act of poetic protest served as catalyst to the installation, which, ultimately, sought to reclaim agency through memory.”

—Tazneem Rezak and Nabeel Essa