The Myth-Science of Blackness

I’m not real. I’m just like you. You don’t exist in this society. If you did, your people wouldn’t be seeking equal rights. You’re not real. If you were, you’d have some status among the nations of the world. So, we’re both myths. I do not come to you as a reality; I come to you as the myth, because that’s what Black people are. Myths. I came from a dream that the Black man dreamed a long time ago. I’m actually a presence sent to you by your ancestors.

Sun Ra, Space Is the Place

Kumbirai Makumbe describes themself using borderless, halfway words. Words like “interchangeably,” “multidisciplinary,” “interdisciplinary.” Halfway words that refuse ease of definition. A London-based, Zimbabwean new media artist, Makumbe is interested in the intangible, the condition of in-betweenness.

“When I first began my practice, I wanted to find this definition of Blackness that was inclusive and representational to everyone,” they explain. “One thing that was really formative [for] my exploration of [Blackness] was Physics of Blackness, by MichelIe M. Wright. In that work, she talks about linear progress narratives, and how linear progress narratives are so singular, and only one directional.”

In Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology, Wright argues that tending to focus on what blackness is can obscure the inherent when and where of blackness, with its shifting meaning over time and space. Wright looks at Black theories of knowledge that stem from what we know and can prove to be true about the Middle Passage. She examines how this knowledge is constructed and the ways in which the parameters of this knowledge may limit an adequately inclusive contemporary understanding of blackness.

Makumbe continues: “A lot of collectivity around blackness is centred around the Middle Passage and the trajectory from that point forward. And so, I think for me, I've just been really drawn to trying to capture the experience of being divergent within the frame of that and being complex.”

Makumbe is part of a collective of African artists who are not only detangling what it means to identify as Black and African, but also what it means to self-narrate as an African futurist. In the first episode of Race Beyond Borders, season 3, host Nigel Richard speaks to Makumbe about Black quantum futures, the multiplicity of Black experiences, and how the digital sphere provides new territory on which to map the multiverse of blackness, beyond the boundaries of Afrofuturism.

The term “Afrofuturism” first appears in a 1993 essay titled “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel Delany, Greg Taten and Tricia Rose” by white American critic Mark Dery. Dery defined Afrofuturism as: “speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century technoculture”. The term has since been revised and renegotiated, expanding in the late 1990s and early 2000s, to delineate a counter-tradition of Afro-diasporic self-identification, media production, and thought that imaginatively challenged whitewashed futures and colonialist histories with Afrocentric, futurist revisionings.

“By framing Black collectivity around the Middle Passage, are you then excluding other Black groupings of people who weren’t necessarily involved within the transatlantic slave trade but were affected by white oppression in other ways?” questions Makumbe.

The Middle Passage occupies the bulk of Black speculative imagination, the horrors requiring something other than realism in order to be accurately represented. In “‘Africa As an Alien Future’: The Middle Passage, Afrofuturism, and Postcolonial Waterworlds”, Ruth Mayer writes: “When reenacted from the perspective of today, the Middle Passage acquires a whole set of new connotations.” According to Mayer, “All of these revisions, as different as they are, concentrate on the fantasy spaces in-between and nowhere at all, spaces that present themselves as mixed-up, ambivalent, floating.”

“By consequence, speculations and fantasies arise which move ceaselessly back and forth through time and space, between cultural traditions and geographical time zones, and thus ‘between Africa as a lost continent in the past and between Africa as an alien future,’” Mayer writes, quoting British-Ghanaian writer Kodwo Eshun.

But Africa is neither lost nor some monolithic relic from a distant past. Almost in retaliation against the Afrofuturist aesthetic of Black Panther’s Wakanda, which locates Africa in one far-removed and stagnant space-time, more and more African artists are shirking the “Mothership Connection Cosmic Funk” philosophies for speculative myth-sciences rooted in other lived and imagined experiences of Blackness.

“I was struggling to find myself within a tradition that already exists. And so, I really started thinking into Black aesthetics, and how web digital work fits into that. That led me into thinking about blackness, or the perception of blackness as one-dimensional,” explains Makumbe.

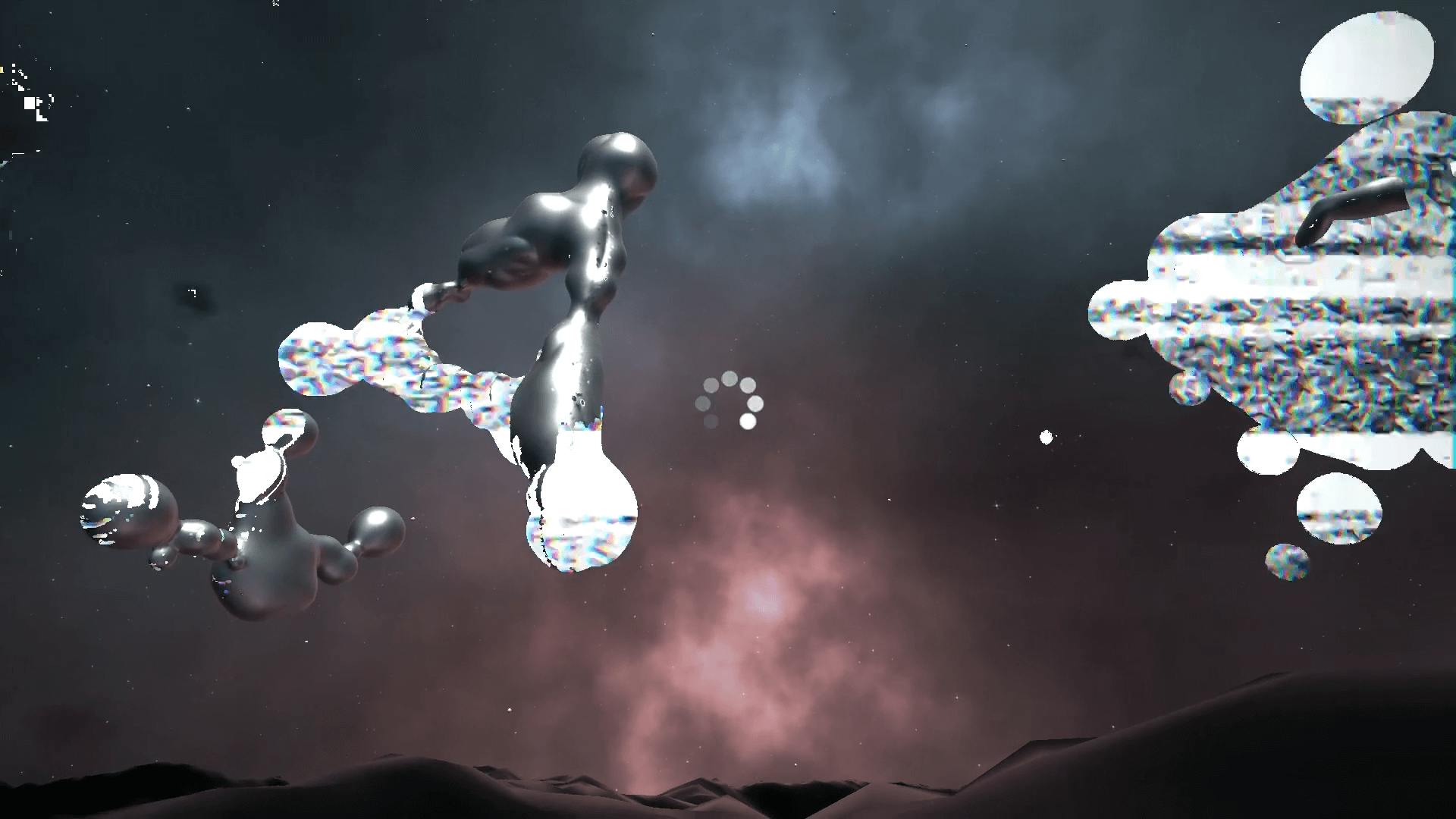

In Makube’s film, Evo’s Turn, Evo is an AI grappling with its own blackness. According to the description of the work, Evo "pans across a barren desert cloaked in night. Within this work, Makumbe removes the body, encouraging the AI to question if it can possess a physical form. Evo personifies blackness as silver sap, an entity that reflects while retaining its own characteristics. Throughout the work, Evo defaults to a loading screen, buffering in a feeble attempt to grasp its relation to the artist despite its lack of sentience.”

The film stemmed from Makumbe’s critiques of Black essentialism.

“I was really interested in trying to bend in opposition to that, and to counter that. [I was] trying to imagine blackness as multidimensional, and how that could be illustrated. I then had this idea of trying to conceptualise blackness as silver. I saw it as abstract; non-physical, intangible, constantly in flux. Non-material, so it's constantly changing shape.”

“Blackness isn’t a colour, Evo describes, it is an idea conceived in relation to whiteness,“ the film’s description continues.

Makumbe’s dimensions are spaceless, timeless. Their work occupies the backrooms of blackness, whose identities shift, morph and evaporate just as quickly as they come into focus. A tension, more than a truth. And it is in these tensions that Makumbe’s self-narrated hypotheses of blackness are spawned, in spaces in between.

“Silver’s reflective, but in a way it's silver. If you put silver in a blue room, it will reflect the blue, but it still remains silver. The way it’s able to appear as something whilst still being its own thing was something I thought really linked to blackness.”

In Evo’s Turn, Evo narrates a monologue in which they are able to speculate and theorise an alternative. Evo describes blackness as “a silver sap oozing out of the entity that is Black mass consciousness. Black collectivity, as Black mass consciousness, as the Black primordial soup through which Blackness can be conceived and excreted.”

Reflecting on the work, Makumbe says, “I put forward an idea of blackness being multidimensional poles and how to visualise that, and kind of creating an illustrative language.”

Makumbe’s work asks: If blackness cannot be dictated by phenotype or pigmentation; if it cannot be located along specific coordinates, longitudinal and latitudinal lines; if it cannot not be collected and assessed as a set of cultures, traditions and behaviours, then how is it defined or determined? Makumbe propose no answers, only wider and more complex sets of questions. Questions that perhaps can only be lived, and not satisfied.