Bridging Black Worlds: South Africa and the United States

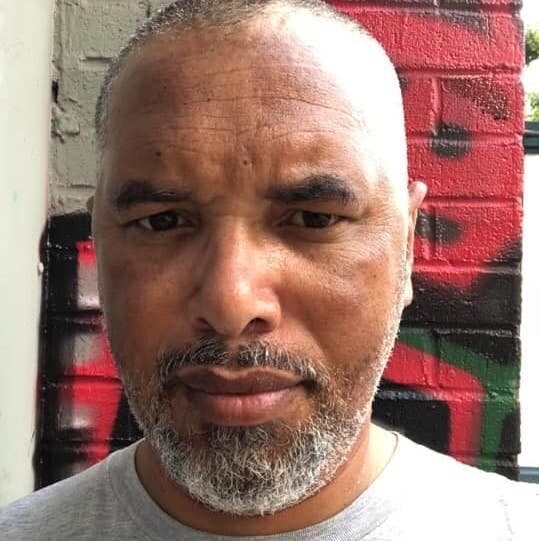

This issue of Moya considers the long history of connections, exchanges, and solidarities between Black people in the United States and South Africa, writes guest editor Sean Jacobs.

This issue considers the long history, some of it forgotten, of connections, solidarities, and exchanges between Black people in the United States and South Africa. Released on the eve of South Africa’s seventh democratic elections in a year that Americans also go to the polls, the issue asks: what is required to strengthen and sustain transnational solidarity between and across Black worlds? Why do we need this solidarity, and what forms will it take? The issue also explores how historical exchanges between Black people in the US and South Africa were valuable and complicated, and how they manifest now.

In guest editing the issue, I drew from my experiences in and between the two countries.

I was born and grew up in Cape Town, South Africa. In my early life, American culture, especially Black American culture, influenced my imagination through film, television, and music like jazz, R&B, and hip-hop. Although I was brought up Anglican and my parents later converted to Evangelical Christianity, which discouraged political activity, I was exposed on the streets to the politicised theology of African Methodist Episcopal (AME) pastors, who would join marches organised by youth movements or provide spiritual guidance to young activists. I was struck by how they were so different from the average white American missionary who told people in South Africa’s townships to obey the government, believe in capitalism, and hope for a better life after death.

In 1995, one year after South Africa’s first democratic elections, I was awarded a scholarship to study for a master’s degree in political science at Northwestern University in Chicago, a predominantly Black city. The mid-1990s was also a period in which Barack Obama emerged in Chicago politics. The end of the Cold War and the hardwiring of Reaganism into policy, marked a shift to a neoliberal class of Black politicians, away from the politics of Harold Washington Jnr., the city’s iconic mayor. Nearly a decade earlier and under a progressive policy platform, Washington had united a broad coalition of Chicago’s working-class and minority communities to propel himself into office. He was also an internationalist, mainly active in the anti-apartheid movement.

In classes on urban and racial politics in the United States, I saw the challenges the new South Africa was yet to face. Adolph Reed Jr, a leading Black political theorist and one of my favourite professors, was among the first American public intellectuals to analyse the rise of a new post-civil rights black leadership whose policy prescriptions shared much with their conservative white counterparts. Reed characterised Obama’s neoliberal politics as “vacuous-to-repressive” and predicted with dismay that Obama represented the future of Black politics in the US. Reed would later write about these politicians who blamed social and economic inequalities on a lack of family structure and Black people’s inability to take advantage of the opportunities presented by free-market capitalism: “I want the record to show that I do not want to hear another word about drugs or crime without hearing in the same breath about decent jobs, adequate housing, and egalitarian education.”

Back in South Africa at the start of 1997, after graduating, I saw the country encounter the difficulties of transforming a racially divided and unequal society into one in which all could prosper. The vitality and high hopes for the first decade of democracy were displaced by cynicism and disappointment as the governing African National Congress (ANC) grappled with the policy straightjacket of neoliberalism but also began to jettison its radical pro-poor policy positions and state institutions buckled under maladministration and corruption, most pointedly under the presidency of Jacob Zuma.

Today, as the country marks thirty years of democracy, much of the opposition of the past decade or so to the ANC’s misrule resembles the political class that Reed first identified in the United States—politicians like the former Johannesburg mayor and now leader of the ActionSA party, Herman Mashaba, who made a fortune from black hair care products—with their scapegoating of immigrants and the poor, and their prescription to privatize public services. It strikes me that even Zuma’s class of politicians fit Reed’s earlier critique of “the Black community” as a concept “that presumes homogeneity of interests and perceptions,” allowing “hustlers of one sort or another” to exploit it to their own ends.

Over the past decade, another tradition drawing lessons from movements that have gone before in both countries emerged. Led by young people and feeding off each other’s energy, Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall demanded a confrontation with apartheid and the American empire’s structural racial legacy, neoliberalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy. While the long-term legacy of these exchanges is yet to become fully apparent, this issue recognises that they represented milestones in a much longer history of solidarity across the Black Atlantic.

In his contribution to the issue, historian Robert Trent Vinson gives us a sweeping history of the influence of African-American-inflected political practices on Black South Africa. Vinson notes broadly similar historical trajectories of racial subordination between the two countries: from colonization in the seventeenth century through conquest, land theft, slavery, and segregation, all accompanied by a corresponding racist ideology. And just as white leaders of both states showed solidarity, so did those who resisted them.

Much of this explicitly radical transnational political consciousness was associated with Black South Africans beginning to study in the US in the late nineteenth century. Then came the AME church’s earliest missions in South Africa and the phenomenal growth of Garveyism in the pre-war period. As Robert writes, “... Garveyites in South Africa expressed their liberationist aspirations and political grievances grounded in a 19th-century prophetic Christianity” that stressed biblical connections to Africa. Ultimately, Garveyism did not lead to Black South African deliverance, but it did deepen the transnational alliance between Black South Africans and Americans. Later, Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement were similarly impacted by African-American liberation theology of the mid to late 1960s.

Focusing on a specific instance of these transnational solidarities, historian Drew Thompson—author of a book on the history of photography in Mozambique’s liberation struggle and the decolonisation process that followed after independence in 1975—looks at the decisive role of Black Americans at the advent of the boycott, sanctions, and divestment movement against apartheid South Africa.

Thompson tells the story of Caroline Hunter and the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers’ Movement (PRWM), a divestment movement that forced US corporations to withdraw from apartheid South Africa. This is a story, not well-known in South Africa or even the United States, of how a mainly African-American workforce at the Polaroid Corporation in the early 1970s, organised under the PRWM, discovered the company was supplying the South African government with the film and technology to make passport photos, including for use in the dreaded passbooks, which were invented to restrict and monitor the movement of Black South Africans. The PRWM led a campaign in the US, including testifying before the US Congress and the United Nations Special Committee on Apartheid. The pressure contributed to Polaroid becoming one of the first major companies in the US to divest from South Africa in 1977.

Hunter told Thompson: “I think for a lot of people who were anti-apartheid activists before we discovered the I.D. [system] at Polaroid, we were a breath of fresh air. Prior to that, it was an intellectual conversation about what people wanted to do. A lot of mobilisation in Europe and around the world …They were all excited about our entry into the fight.”

The third and final feature piece catches us up to the present. Khanya Mtshali, a South African writer based in Johannesburg, reflects on Trevor Noah, who, after Nelson Mandela, is the most recognisable South African public figure in the United States. Noah’s standing now differs from when he first entered US public culture, largely thanks to his unlikely hosting of The Daily Show,” the American comedy news show, between 2015 and 2022.

Initially an admirer, then more critical and now ambivalent of Noah, Mtshali reminds us that a huge part of Noah’s success in the United States has come from weaving his mixed-race heritage and outsider status—even in his native South Africa—into his personal branding and comedy. In the process, he has sought to position himself as a voice of reason able to poke fun at everyone equally. But this approach to comedy is possible only when ignoring social history and, as the case of Noah shows, it invariably “ends up siding with the powerful and making fun of the vulnerable,” Mtshali writes.

As this issue came together, we also got a glimpse of another way for South Africa to be in the world, one that both expands and draws on this long history of solidarity, stoking hopes that the country could, following the death of Mandela and, more recently, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, still live up to its potential as the moral voice on the global stage: In January 2024, South Africa’s government lodged a genocide case at International Court of Justice in The Hague and secure provisional measures against Israel for its actions in Gaza. In so doing, South Africa aligned with the Global South, attracting allies from Ireland and Bosnia, and emboldened others to lodge cases against Israel and its ally Germany. South Africa asserted a marker for global civil society and a new kind of global politics in holding international institutions accountable. The venerable Black American thinker and activist Angela Davis, drawing on the long connection of her people with South Africa, told a journalist: “The fact that South Africa stood up to represent Palestine [at the ICJ] has created new hope in the world. And those of us who felt that we had invested so much in the struggle against apartheid and then felt let down, we can now look at South Africa and its alliance with Palestine on the world stage and say that it was worthwhile to engage in all of those years of struggle to dismantle apartheid.”

More from this issue